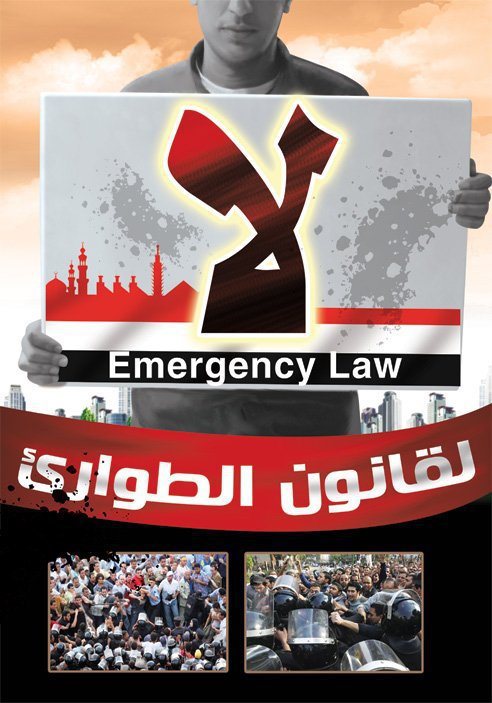

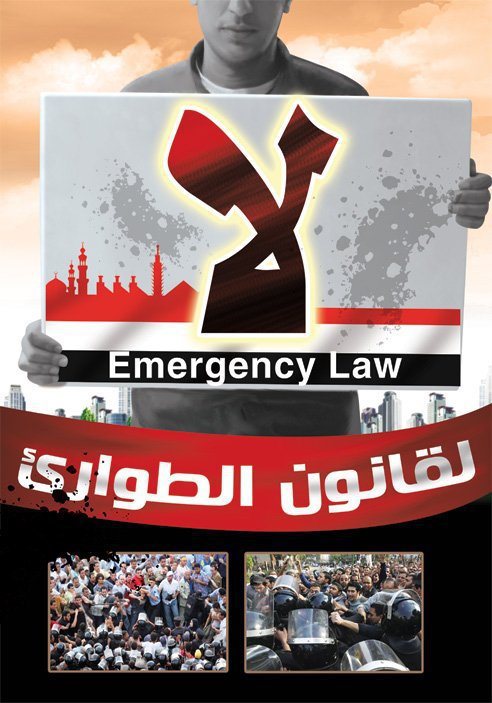

It is no secret that Egypt is living through a critical transitional phase in the aftermath of the 25 January Revolution; a chapter replete with abnormal conditions and events that warrant temporary, exceptional policies. The magnitude of the risks now threatening the homeland renders extraordinary decisions fully understandable. I say this in response to the wave of angry protest which swept the Egyptian scene in the wake of the decree enacted by the ruling Supreme Council of the Armed Forces to enforce the emergency law in specific, given cases.

It is no secret that Egypt is living through a critical transitional phase in the aftermath of the 25 January Revolution; a chapter replete with abnormal conditions and events that warrant temporary, exceptional policies. The magnitude of the risks now threatening the homeland renders extraordinary decisions fully understandable. I say this in response to the wave of angry protest which swept the Egyptian scene in the wake of the decree enacted by the ruling Supreme Council of the Armed Forces to enforce the emergency law in specific, given cases.

The emergency law: Trap or protection?

Youseef Sidhom

Opinion

00:09

Sunday ,25 September 2011

The post-revolutionary times are seeing exceptionally high crime rates, rampant acts of thuggery, frequent incidents of terrorising peaceful civilians and seizing their property in broad daylight, incessant attacks on public facilities, widespread cases of road blocking, a thriving arms trade, unbridled possession and use of unlicensed weapons, to mention but a few. Yet a host of politicians and pundits rose up in protest against the enactment of the emergency law, inundating us with angry statements claiming that civil law includes provisions sufficiently capable of protecting the public and the nation—as though all the crime and unrest were ‘normal conditions’ that warrant no extraordinary measures.

I firmly believe that such manipulation of democracy and human rights to promote the notion that the ruling authorities seek to exploit the situation to oppress opposition ought to be halted. Proponents of those arguments are well aware of two facts: first, the implementation of the emergency law should be restricted to the criminal acts specified by the decree; second, the disarray over the past seven months has reached frightful levels. The upcoming electoral season poses added risks; left unchecked, the situation could be ripe for acts of terrorism, thuggery and violence that could entirely demoralise the nation.

None of the vociferous opponents of the enactment of the emergency law offer any effective alternative to rein in the disarray. As they criticise the emergency law they, in the same breath, vehemently decry the now-familiar unchecked crime. But they fall short of offering substitutes for the hated emergency law.

The damning attitude strongly calls to mind two recent episodes. The first was the wave of Islamist protest that erupted a few weeks ago against the institution of governing principles for Egypt’s new constitution, under the claim that this would hijack the will and sovereignty of the public. Neither were the proposed principles objectively debated nor was any reasonable discussion conducted to confirm the preposterous claim.

The second was the ruckus created by the proposition of rules to govern the selection of the members of the constituent assembly that would be charged with drafting the new constitution. Those who created the commotion cast themselves as the guardians of the people’s right to formulate their own constitution—as though the rules excluded the people from drafting the constitution and brought in foreign ‘experts’ to do the job. They did not even bother to scrutinise the proposed rules to tell us exactly why they opposed them, given that these rules guarantee a balanced representation for all the various forces and groups across the social and political spectrum, with the exclusion of none. They never said how this could be a conspiracy to prevent the public from exercising their right.

The forces which take it upon themselves to wage these hollow campaigns with the aim of deceiving the public while pretending to have the good of the homeland at heart have but one objective: to monopolise the decision-making process to promote their own agenda. It is now eminently obvious that these forces care nothing for formulating fine constitutional principles for the good of the nation; neither do they have any interest in balanced representation of the various national groups to draft the constitution. They appear bent upon hijacking the current phase to their own ends.

The major challenge confronting Egyptians today is to properly investigate the political map to define their position. We should spare no effort to examine options and alternatives, so that when the hour of reckoning comes we would cast our votes to forge the future of Egypt. We should be cautious not to fall prey to fear or panic, and remember that some forces are keen to keep us at home instead of heading to the polls. And the emergency law should rein in the violence, chaos and crime that used to prevent large numbers of voters from casting their ballots in the past. What we have at hand is not a conspiracy to victimise critics of the authority. It is a provisional measure to safeguard the people and restore security on the Egyptian street, in order to successfully traverse the transition we are going through.