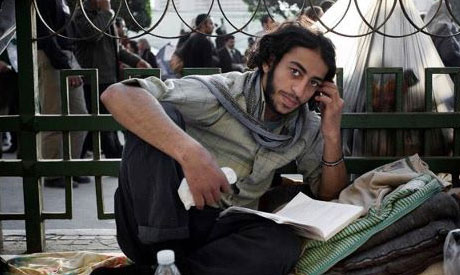

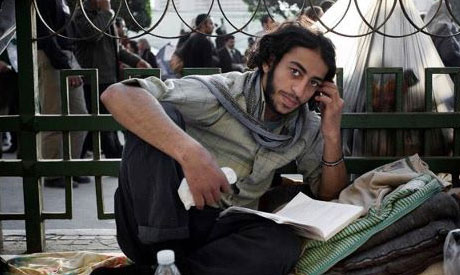

Tarek El-Tayeb, 25, had always hated Christians. He was known among his friends as Tarek “El-Salafi” as he followed the ultraorthodox school of Islam.

Tarek El-Tayeb, 25, had always hated Christians. He was known among his friends as Tarek “El-Salafi” as he followed the ultraorthodox school of Islam.

"I joined the Salafist school of Islam when I was 13 years old," remembers El-Tayeb. "According to my ideology, Christians were heretics and being a friend with any of them was a grave sin."

All of this changed when he met Coptic Christian activist Mina Danial.

The two bumped into each other in Cairo’s iconic Tahrir Square during last year’s 18-day uprising.

They met the morning after the 28 January "Friday of Rage", when Hosni Mubarak’s security forces fired tear gas, rubber bullets and live ammunition at protesters. Danial had been shot in the leg.

"Are you injured?" asked El-Tayeb.

"Yes," laughed Mina. "But it's not a big deal."

"No, it's not ok," responded El-Tayeb. "You need to clean that wound."

El-Tayeb insisted and took Mina to the nearby Qasr Al-Eini Hospital. After that, the two, became inseparable.

"Mina and I didn’t go through the normal stages of friendship," remembers El-Tayeb. "After the first few minutes we became like brothers."

Despite the closeness of the two, El-Tayeb still struggled to overcome his discomfort at having a Christian friend.

"I never told him how I felt about Christians," says El-Tayeb. "He would sometimes tell me that he loved me and I would respond by saying that I hate him. It was just hard for me to get rid of these fanatical ideas all at once. It took time."

Since becoming a Salafist, El-Tayeb made sure he was civil to his Christian neighbors and colleagues, however, being friends with a Christian was simply out of the question. Danial was different.

"I just could not hate him. For the first time in my life, I found that I could not hate a Christian. I could not put this barrier of religion between me and him," El-Tayeb explains, "The emotions I felt towards him destroyed all of these shackles. I didn’t understand it then and I still don’t understand it now. What is it about Danial that made him have this impact on people?"

Mina was special, his friends say, unique, charismatic and impossible to hate. He was a cheerful young man, who was always smiling and had the uncanny ability to win people over.

Mina Danial at a downtown Cairo protest after the 18 days (Photo: Facebook)

Mina, the youngest of seven, was born in the town of Sanabo in the Upper Egyptian governorate of Assiut. He was raised mainly by his sister Marry, 21 years his senior. He was so close to Marry that he called her "mum."

"He was born at ten in the morning,” recalls Marry, who looks strikingly similar to her brother, smiling at the memory. "He was such a beautiful child. For me, he was a son and not a brother."

The Danials were the only Christian family in a street of Muslims.

Life was good initially, Muslims and Christians got along well, says Marry.

However things changed in the mid-1980s when sectarian tension began to spread throughout Egypt, as ultraorthodox Islamic groups gained power. Life for Christians changed forever.

"I remember we were a group of seven girlfriends living in the same street. We were very close," Marry says. "Then one day, I walked to the bus stop as usual to meet them and I noticed that they turned their backs on me and wouldn’t say hello. Fundamentalist groups had succeeded in filling people’s minds with hate."

Slowly, the gap between Muslims and Christians increased, Marry says.

Attacks on Christian homes became common. The Danials were not spared: several members of the Danial family were attacked. Marry recalls stones being hurled at her when she walked to church.

One day, a member of the Danial family got into a fight with an Islamist, after the latter demanded that he turn off the Christian Mass that was playing on the radio. The fight escalated and the family went to lodge a complaint at the local police station.

They were shocked when the police responded by arresting nine members of the Danial family instead.

"The fact that they arrested us just because we complained, opened my eyes and made me realise that the regime was collaborating with these fanatics," explains Marry.

By the time Mina was born in 1991, the damage to Muslim and Christian relations had already been done.

The Christians now lived in what Marry called "Church isolation."

"The church became a state within a state," says Marry. "It ran supermarkets, hospitals, clubs, picnics, lectures, everything. Our whole life became centered around the church."

The violence continued. When Mina was two years old, the family decided to pack up and head to Cairo.

They settled in the suburb of Ezzbet El-Nakhl, where Mina lived until he died.

A quiet child, he spent most of his time with his sister Marry, who used to take him, along with his other sister Sherry, who was four years older than him, to church.

"Everyone at church envied me for having him. He was so quiet and sensitive. He never whined and would not ask me to buy him anything because he would worry that I would not have enough money."

Proud of his Pharaonic heritage, Mina dreamed of studying archeology one day but his results were not good enough. He opted for a Bachelor of Commerce instead.

"He wasn’t very happy though and always dreamed that one day he would find a way to enroll in the college he wanted," Marry says.

In his teens, Mina slowly began to get involved in politics.

Coptic Christian rally against discrimination in Egypt (Photo: Reuters)

He started frequenting downtown Cairo, the popular haunt of Egypt's political activists. He developed an interest in Argentine Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara.

Physically, he copied Guevara; the hair and clothes were styled after his hero. Politically, he leaned towards the left. He felt that socialism was the solution to Egypt’s poverty.

However, it was Guevara’s quest for social justice that gripped Mina the most. His close friend, Ramez Sobhy, says that Mina was impressed by the revolutionary leader's struggle to help the poor.

"Mina always used to say that Egypt’s poor were like a football constantly kicked between the Islamists and liberals," says Sobhy. "People always think of Mina as a Christian martyr but that is not true. Mina was a martyr of the poor. It was the plight of the impoverished that concerned him the most."

It is not difficult to understand why. Ezzbet El-Nakhl, where Mina lived, is one of the most poverty-stricken areas in Cairo. The misery is devastating. Roads that lead to Mina’s house are dusty and broken, the buildings are rundown.

A few roads away from his house, young children play on a swing, precariously balanced over a titanic pile of rubbish and rubble.

Mina was not looking for a way out for himself only, he wanted a collective solution that would benefit all of Egypt’s poor.

He began encouraging his friends to go on trips to Egypt’s underprivileged areas to talk to the people and discuss possible solutions for their problems. He attended meetings held by various political movements in Egypt but none satisfied him.

"Mina did not trust these political groups. He felt that the solution was in the hands of the poor," explains Sobhy. "He felt that Egypt’s poor should unite and help each other and fight for their rights."

After the 2010 Nagaa Hamadi attack, during which armed gunmen killed eight Christian worshippers as they were emerging from a Christmas Mass in the Upper Egyptian city, Mina’s activism amplified.

He joined the Justice and Freedom Movement, a youth group that was calling for change.

Despite being heartbroken over the deteriorating situation for Christians in Egypt, friends say, Mina did not have sectarian tendencies. He always believed that the Christian problem was part of the bigger Egyptian problem.

"Whenever sectarian problems take place, he would ask me, why do they always happen in poor places, why do we never hear of Muslims and Christians fighting in rich areas like [Cairo's central district] Zamalek?" Sobhy adds.

Mina resented Christian-only protests and sit-ins. He would tell his friends that carrying crosses and chanting Christian slogans might discourage Muslims from participating. He believed that unity was the key.

In one incident that Sobhy recalls, the residents of Cairo's working-class district Bulaq clashed with Christians who were protesting against discrimination. Mina went to talk to them.

"He told them, why are you fighting each other? Both Muslims and Christians are poor, both can’t find proper housing, both are suffering," says Sobhy. "In the end, the Muslims joined the Christians in the protest. Mina had that kind of charisma. His effect on people was monumental. When he talked, people listened."

Military vehicles charge at protesters in front of Maspero TV headquarters (Photo: Reuters)

Tragedy struck again on New Year’s Eve in 2011, when a bomb exploded in the Two Saints Church in Alexandria minutes after midnight, killing 25 civilians. That night a distraught Mina drove to Alexandria.

"He saw the shredded bodies; he saw a human scalp hanging on an iron rod," remembers Marry. "He was in shock. He refused to eat for a week after that."

When the January 25 Revolution took off, Mina and his friends joined the mass sit-in on Tahrir Square.

Mina was renowned for being fearless: he would often be seen fighting the security forces on the front lines. As a result, he was repeatedly wounded. He was shot in the leg with a live bullet and suffered countless other injuries across his body.

When Mubarak stepped down on 11 February, Mina, who had gone home to change his clothes, rushed to the flashpoint square and danced with his sister.

However, the situation in Egypt did not improve.

On 9 March, just weeks after the military council assumed power, the army forcibly dispersed a Tahrir Square sit-in. Churches were attacked and torched.

Egypt's political dialogue began to change. Islamists, denouncing Christians as heretics, gathered support. However, Mina was an eternal optimist, his friends said.

"Whenever we felt demoralised or sad, we would call him," says Sobhy. "He would give us an energy boost."

He continued to attend all the post-uprising protests, which demanded the fulfillment of the revolution’s demands.

Early April, he joined a mass protest calling for ousted president Mubarak, who at the time was still free and living in the Red Sea resort Sharm El-Sheikh, to be put on trial. This is where Mina met the love of his life, Katherine.

The petite brunette, 29, has not spoken to the media since Mina died. She finds it hard to talk about him, without breaking down, she says.

Katherine, like Mina, came from a conservative Upper Egyptian Christian family. She works as a tour guide and lives in Cairo. The nine-year age difference was a big problem for their families.

"I was shocked when I found out how old he was," smiles Katherine, "but Mina didn’t care. He was not concerned with how old you are, or what your political ideology is. These barriers that humans put against each other were insignificant to him."

A few months after they met, Mina told Katherine of a nightmare he had. He dreamed that black dogs were attacking him, trying to kill him.

Christian woman mourns on the coffin of activist Mina Danial killed at Maspero protest (Photo: Reuters)

The dream occurred on 9 October, 2010. Mina died on 9 October, 2011.

"I knew that Mina was going to die and so did he," says Katherine. "We both felt it."

Attacks on Copts escalated and several sit-ins protesting the increased discrimination towards the Christian community were violently dispersed.

Finally, on 9 October last year, activists decided to hold a peaceful protest.

The march was to begin in the central Cairo's Dawaran Shubra Square and would then head to Egyptian state media headquarters, Maspero. There was no plan for an open sit-in that day. The goal was to reach the radio and television building, make their demands heard and then leave.

People began gathering in Shubra at 4pm. There were many activists but just as many women, children and elderly people. That day, Mina had lunch with his sister and Katherine, before heading to the protest.

He and Katherine walked at the front, while Marry remained in the back. The march continued peacefully for an hour until unknown assailants began hurling stones at the protesters.

At that point, a panicked Marry tried to call her brother repeatedly. Finally, after several attempts, he picked up.

"He told me that he was ok and not to worry," says Marry, "that was the last conversation we had."

Katherine, who was with Mina at the frontline, says that he was in a really good mood.

"The closer we got to Maspero, the better his mood became," Katherine recalls.

However, once the march reached Maspero, the army attacked the demonstrators, using an unprecedented level of force.

Tear gas and live ammunition were fired. Army trucks ran over protesters, mutilating and killing those in the way.

Marry, who had also reached Maspero, described the horror scene.

"To say they were brutal would be an understatement," she says. "I remember that an army truck was trying to run us over. We ran onto the pavement in an attempt to escape them, so the truck driver drove over the pavement in order to get us."

The injured and the dead began to fill up the nearby Coptic hospital.

Katherine, still with Mina, could no longer control her terror.

"My legs began to shake with fear," she says. "So Mina told me that if I was that scared then I better leave. He carried me out of the Maspero area and took me to my father. He told us to take care of each other and left."

Fifteen minutes later Mina was gunned down. He was shot in the shoulder with a single bullet. He was just 19 years old.

His friends informed his sister and fiancé of his death.

Marry visited her brother’s body at the Coptic hospital where the dead were laid out and was surprised that even in death, he was still smiling.

"The fact that he was still smiling made me believe that Mina is not dead. That his dreams will never die."

She kissed him, soaked a cloth in some of his blood and left.

Coptic woman mourns her dead at Coptic Hospital after Maspero (Photo: Reuters)

It was El-Tayeb who refused to leave Mina’s body.

"I sat beside him for two hours and held his hands," El-Tayeb says. "I wouldn’t leave until a mutual friend of ours dragged me out."

After his death, Mina became one of the icons of the revolution.

His face has become a common feature in most revolutionary murals. Demonstrators wear masks of his face or hold aloft placards of his image during marches.

Both President Mohamed Morsi and his rival regime-figure Ahmed Shafiq used Mina’s image as part of their presidential electoral campaigns.

His sister Marry has become as familiar a figure as her brother. Revolutionaries seek her presence in their protests and marches to give them credibility and to gain public attention.

"Maybe I have become a symbol of the families of the martyrs, who are still struggling for their rights. Or maybe I remind them of Mina," smiles Marry.

She is also active online. She has 5000 Facebook friends and laughingly adds that she has 1000 more pending friend requests.

However, Marry insists that her main purpose in life now is to get justice for Mina. To date, no one has been found responsible for the deaths of the 27 protesters, killed on 9 October.

Marry is determined to continue Mina's quest for social justice.

"I want to see the day when no one is sleeping on the pavement. The day where no one is living in the tombs or searching for food in the garbage," says Marry. "This is what Mina wanted."

Some of Mina’s friends however, feel that politicians abuse his name for their own benefit.

"The Muslim Brotherhood, for one, are all hypocrites," fumes El-Tayeb. "On a personal level they call Mina a heretic, but publicly, they claim that he is a martyr."

El-Tayeb has abandoned Salafism since Mina’s death. He now considers himself a "moderate Egyptian Muslim." He is proud that he now has many Christian friends.

"Mina opened the door for me. He taught me what humanity meant," says El-Tayeb. "He opened my eyes and I finally saw Christians as they really are: good people, kind, charitable and not corrupt as the extremists claimed."

As for Mina, everyone loved him.

"How can a man win so many hearts, unless God loves him?" asks El-Tayeb. "There is only one Mina."