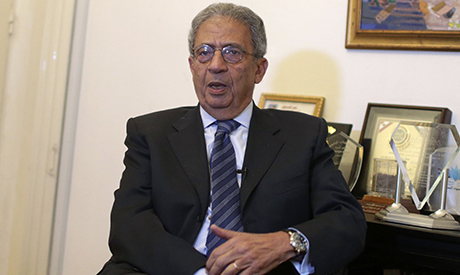

It was around this time last year that Amr Moussa announced that his meeting with the Muslim Brotherhood kingpin Khairat El-Shater failed to find a negotiated exit out of the political deal.

It was around this time last year that Amr Moussa announced that his meeting with the Muslim Brotherhood kingpin Khairat El-Shater failed to find a negotiated exit out of the political deal.

“When I look back I am still convinced today that it was not at all possible to reach a deal with the Muslim Brotherhood simply because of their intransigence; they were not willing to give in to any of the people’s demands especially the one related to the early presidential election; they had a mental block; they made the 30 June inevitable,” Moussa told Ahram Online.

“The 30 June demonstration could not have been avoided not because anyone was predetermined to ouster Morsi but because Morsi and his group had decided to shrug the public demands and to act according to their own agenda; it was impossible to let things go the way they were – not with the enormous mismanagement of state affairs that the Muslim Brotherhood had shown,” he said.

Having been the target of the anger of the anti-Morsi National Salvation Front, of which Moussa was a leading member, and the media, at the time for trying a last ditch attempt in favour of a negotiated deal Moussa today is willing to acknowledge “some errors” on the part of the NSF in managing the political choices post 30 June. “We cannot claim that we were all right all the way through.”

Moussa does not blame Mohamed ElBaradei for rejecting a referendum on the ouster of Morsi in what could have, as critics suggest, blocked the debate over whether or not the ouster was legitimate.

“30 June was a revolution; there are no two ways about it; it was a revolution in every sense of the world,” Moussa argued.

He categorically denied that it opened the door to “the rule of the top brass.”

“I don’t at all like this phrase; it is incompatible with the creed of our armed forces and with the way things are on the ground; the military are not ruling and have not been ruling since the ouster of Mohamed Morsi; the state and not the military has been in charge,” he said.

“And the fact that the current president is former military does not mean that the country is ruled by the military; this argument does not make sense.”

According to Moussa, “what we saw on 3 July (when El-Sisi announced Morsi was being removed) was a decisive decision that was taken to avert chaos and turmoil.”

“At that point in time hesitation was absolutely unaffordable; we had the roadmap and we are already done with two steps and we are moving on to the third.”

According to the roadmap announced by El-Sisi, in the presence of ElBaradei and other politicians from the opposition but not Moussa, Egypt to see amendment of the constitution that was voted in under Morsi, then to have legislative elections and lastly to have the presidential elections.

Moussa was at the head of the committee that reworked the constitution, which was later adopted by national referendum.

Adly Mansour, who was chief of the Supreme Constitutional Court and was assigned to take over the top executive role during the transitionary phase. Mansour issued a decree to allow presidential elections first, following the argument made by some that the delay in the presidential vote was allowing for too much uncertainty and harming an already ailing economy.

Preparations are now under way for parliamentary elections.

Moussa, himself a former presidential candidate who came fifth in the vote that Morsi won in 2012, delined to either confirm or deny that he would be running at the head of a civil-democratic list to be elected MP and then to contest the speaker’s seat.

At this point in time, Moussa is confining himself to talk of the “consultations to launch a coalition for the civil democratic forces that share the wish and the will to build a modern democratic Egypt, and who come from all walks of life – with no Egyptian citizen excluded for any reason other than proven, and not just alleged, legal wrong-doing”.

Contrary to media speculation, Moussa firmly denies that a coalition was being built but was later aborted. “None of this is true; we are still exploring our options but no coalition has been made and no coalition has collapsed as I have read in some news coverage,” he said.

Moussa also denies what has been “suggested by some unfortunate and inaccurate media coverage on the part of some” that the new political coalition is designed to lend parliamentary support to the new president, who unlike his predecessors, according to the new constitution, would need to rely heavily on the parliamentary majority to form a government and to pass new laws.

“I myself have not spoken with the president, not even before his inauguration, of this parliamentary matter and he had not asked for all I know for the formation of a political coalition to lend him parliamentary support,” Moussa said.

This said, Moussa hastened to add, “we should all be working in a positive and constructive way; this should aim to the support of the president’s scheme to rebuild Egypt following the criteria stipulated in the constitution and the will of the people, as has been expressed since the 30 June and up until the presidential elections: a free, civil, strong and democratic Egypt where all citizens are equal before the law and where development is pursued to serve the interest of the citizens.”

“But this is not to say that the entire parliament would be or should at all be fully on one side – there will certainly be opposition; obviously this is the way democracy is,” he said.

Moussa is convinced that the election of the new parliament is a crucial step in the post 30 June political process. “It is this parliament that would make sure that the text of the constitution is translated into laws that would be passed with the accord of the representatives of the people.”

The new parliament, Moussa argued, would be in charge of addressing some of the current problematic issues including for example the controversial demonstrations law that has been qualified by human rights groups as repressive and that has allowed for the arrest of activists both Islamist and secular – including many who had been in the forefront of the call for the 30 June protest.

“I am not going to deny that there has been some problematic legislation, but I am willing to argue that it is up to the new parliament to address these matters and to create the right setting for an efficient state management that recognises human rights and freedoms, which are clearly stipulated in the constitution, socio-economic rights, security and so on.”

Moussa is willing, ever so reluctantly, to acknowledge some signs of repression, without saying the word.

The politician, who has been very supportive of the nomination and election of El-Sisi, is firm in denying any responsibility of the president for the violations that have been recorded. Nor does he agrees with all of the complaints.

“I don’t think you can blame someone who has barely been in office for three weeks for every single error that occurred; also I don’t think it makes sense at all to extract the issues at discussion out of the wider disturbed political context. I am not saying here that I condone any wrongdoing under any pretext but I am clearly saying that we are in the phase of reassembling a state that was being dismantled and that there are mistakes and that these mistakes would have to be rectified – through the right channels, including the new parliament.”

Moussa, who was foreign minister in the 1990s under former president Hosni Mubarak, also denied that the country is going back to the norms of the Mubarak rule.

Repression of protests, intimidation of opposition, political censorship and control of the media are qualifications that Moussa firmly disagrees with.

“You cannot say that these qualifications apply – not even if you look at the picture from the darkest angel. There are mistakes,” Moussa said. “And you cannot compare the situation today to what it was before the 25 January Revolution – because there has been the 25 January Revolution and there has been the 30 June which will always be a strong reminder of the consequences of state mismanagement,” he added.

At the meantime, Moussa does not shrug off questions about whether or not there is a reason to worry. “Of course we have to worry for the future and we have to be alert that things are done right, but this is different from being addictive skeptical.”

“We have a daunting challenge; the president as I know him and as I heard him is committed to do what it takes for success to be on our side; he knows he cannot afford to fail and nobody should want him to fail; it is not in the interest of any of us; it is not in the interest of the country,” he said.