Everyone is in one boat and instead of moving forward, some parties are insisting on remaining at square one. These contradictions and disparities among Arabs have today become commonplace.

Naturally, differences in approach on issues do not mean the end of the world. What is a topic of difference and dispute today could become a beneficial matter where interests and principles converge in the future. What is important is for differences not to escalate into sanction and miscalculation.

Disparity creates polarisation and attracts supporters, which triggers a cycle of push and pull to create two rival axes instead of becoming two camps for stability, security and common interests. The most recent attempts at polarising the Arab world was not from within the Arab realm, but on the African stage. I am referring to the withdrawal of seven Arab countries – including four Gulf countries, alongside Jordan, Djibouti and Morocco – from the summit in Malabo in Equatorial Guinea.

The official reason is because the African Commission did not take into consideration Morocco’s request that the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) — which Rabat does not recognise — should not participate. It was supported by the abovementioned countries, on the basis that the so-called SADR is not a member of the UN.

The reality is that the withdrawal of those Arab countries was primarily the result of a Moroccan-Gulf understanding that was confirmed in April at a meeting in Riyadh linking the future of the Gulf and Morocco, but not necessarily creating a united Arab position.

Accordingly, it did not impact the Arab-African summit that traditionally meets with the participation of 11 Arab countries and Palestine. This saved the summit, gave weight to its work and served as evidence that there are Arab countries, including Egypt, Kuwait, Mauritania, Algeria, Tunisia, Sudan, Lebanon and others that believe that participation is important, and that propelling the Arab-African bloc forward is the correct decision. They also believe that raising the SADR flag – which was not even invited to the summit – is not justification for collective Arab withdrawal that would certainly negatively impact Arab-African relations for years to come.

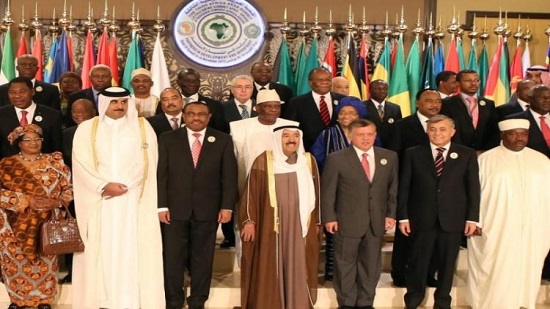

A positive outcome is that the fourth Arab-African summit, the first to be held in an African country after three previous gatherings (Cairo 1977; Libya 2010; Kuwait 2013), concluded its meetings with the attendance of 10 Arab countries and the secretary general of the Arab League.

It issued the Malabo Declaration that expressed support for the Palestinian cause as one for national liberation by a people seeking their legitimate right to an independent sovereign homeland. The declaration also highlighted the importance of focusing on an effective African-Arab partnership to serve the goals of sustainable development in a balanced and comprehensive manner.

The important point here is that African recognition of SADR does not mean Arab recognition of the state – except by Algeria, as a form of political pressure on Morocco to agree to the demands of the Polisario Front to hold a referendum on self-determination for the Sahrawi people as a final solution to the battle between the front and the Kingdom of Morocco. On the other hand, Rabat believes in the unity of Moroccan territories and only granting the front or Sahrawi people extensive autonomy under Moroccan sovereignty.

In Africa, there is absolute support for what they view as the right of the Sahrawi people to establish their own state, which they have recognised and is a member of the African Union, viewed as a co-founder of the union. Almost all AU members view the Sahrawi issue for Africans as the Palestinian cause is for Arabs in terms of importance — as a principle of conscience and humanity.

For Africans, it is an issue of national liberation and self-determination. The irony is that Morocco, after withdrawing from the African Union 32 years ago, is now asking to rejoin the AU and its institutions, and views the move as an expression of Morocco’s desire to restore its natural place in the organisation, but without abandoning its rights in the Western Desert.

Morocco, of course, knows that accepting its membership would require a vote by the AU Commission – after confirming that Rabat upholds all AU documents that affirm the right of Sahrawis to establish their own country. This is something Rabat rejects outright.

The question is: how will Morocco play a developmental role in Africa if it rejects key clauses in AU documents? It is a perplexing question, but confirms that withdrawing is not a solution to any problem. It is a serious risk for those taking it, and will lead to one chasm after another that will be difficult to bridge as time passes by, such as Morocco’s return to the AU after 32 years.

Thus, calculated engagement on any issue, no matter how complex or diverse, is the best and worthwhile path. Accompanied by a readiness to defend principles to the limit, but also to show flexibility in movement and action as much as possible.