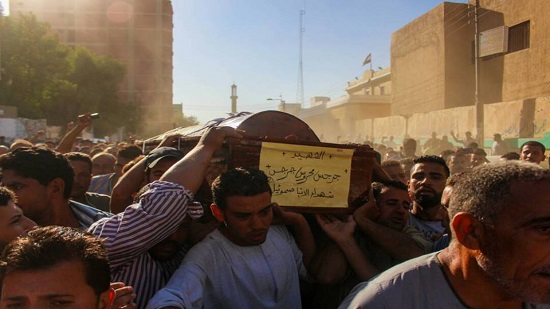

“We never dreamed our brother Mina would be a martyr. He s a hero, a saint just like Mar Girgis, and Mar Mina,” declares Mina s sister, Dimyana Fouad, in the wake of his death in the Palm Sunday bombings in Alexandria earlier this year. Huddled in one of their home s two rooms, the family passed a blood-soaked shirt around.

The blood is the son s, the shirt the father s. “I held him in my arms,” his father says, choking up.

Mina s wife, daughter, parents, and brother — who was also wounded in the bombing — along with members of the extended family, speak about the incident, taking turns to wrap the shirt around their bodies.

“He healed my knees,” says Yoliana, another one of his sisters. “I ve had bad knees for a long time, and I would often complain to him about it. Last night, he appeared to me in a dream, and when I woke up the pain was gone, all gone.”

Martyrdom and the Coptic Church

Apparitions and accounts of miraculous healing, like that of Yoliana, are very much part of folk Coptic culture and are usually associated with canonized saints and martyrs. Relics of martyr saints occupy the entrances of Coptic Orthodox churches, where they are displayed behind glass counters in wooden boxes wrapped in crimson cloth.

Commemoration ceremonies for martyr saints borrow from the burial rites of Jesus described in New Testament accounts. Churches housing relics of martyr saints often become sites of pilgrimage, and believers frequently pray to them for intercession in their troubles, sharing among themselves the miracles performed by saints and martyrs in their daily lives.

Evelyn Said, 53, whose brother-in-law was killed in the Palm Sunday bombings in Tanta this year, believes that “martyrdom is an integral part of our faith.” She describes growing up in a small town between church and family. The body of Martyr Saint Sedhom Bishay was on display in her church. He is the martyr she most relates to — “I consider myself his daughter.”

“The martyrs in Tanta will have a church named after them, and their stories will be published. They will enter the Synaxarium!” she exclaims.

During Church services, as part of the liturgical mass, there is a reading from the Synaxarium, a calendar-style volume of books made up of hagiographies of martyr saints arranged by the date of their death. The date of a martyr s death is considered to be the date of their heavenly birth into eternal life.

Priest Yacoub, who serves in the Deir al-Garnous parish — which recently lost seven men in the mass shooting in Minya on May 26 this year — relates the story of one of the Synaxarium s first authors. Himself a Christian, he would follow other Christians on their way to bear witness to their belief in Christ in the Roman courts. They would be sentenced to death, and he would take their bodies back to their hometowns and document their stories.

Priest Yacoub defines martyrdom in the Coptic Christian faith as, “bearing witness to Christ through holding onto the Christian faith in all circumstances, including persecution and discrimination.”

According to early Christian teachings, to present martyrs to Christ is a source of pride for any church, as death and martyrdom for one s faith is considered the highest form of communion with Christ. This can be seen in the common naming of churches after canonized saints, and recent moves to rename churches that have suffered sectarian deaths in their own congregations.

When a Copt dies, it is common for the immediate family to get a photograph of their loved one photoshopped onto a heavenly background along with images of Jesus and other canonized saints and martyrs. This is later printed for use, particularly in religious ceremonies commemorating the death, including prayers that take place three days and 40 days after the death.

In the event of sectarian killings, these posters take on special significance, and are circulated both online and in print. Extended members of the community often create these posters as a form of tribute to the dead, and to emphasize their martyrdom status.