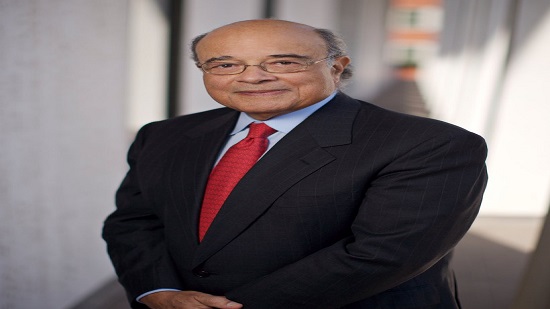

Dr. Adel Mahmoud, an infectious-disease expert who played a vital role in the development of lifesaving vaccines, died on June 11 in Manhattan. He was 76.

His death, at Mount Sinai St. Luke s Hospital, was caused by a brain hemorrhage, his wife, Dr. Sally Hodder, said.

As president of Merck Vaccines from 1998 until 2006, Dr. Mahmoud oversaw the creation and marketing of several vaccines that brought major advances in public health. One prevents rotavirus infection, a potentially fatal cause of diarrhea in babies. Another protects against human papillomavirus (HPV), which causes cancers of the cervix, anus, genitals and middle of the throat.

Dr. Mahmoud also helped usher in a combination vaccine against measles, mumps, rubella and chickenpox, and one to prevent shingles, the painful and debilitating illness that can develop when a previous chickenpox infection is reactivated.

The rotavirus and HPV vaccines were contentious subjects and might never have reached the market without Dr. Mahmoud s determination, said Dr. Julie L. Gerberding, an executive vice president at Merck & Co., and former head of the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. She joined Merck after Dr. Mahmoud retired but described him as a “lifelong mentor.”

Dr. Mahmoud championed those vaccines because he recognized their potential to save lives, she said. Globally, cervical cancer and rotavirus infections kill hundreds of thousands of women and children every year.

The problem with a rotavirus vaccine was that another company had already developed one but then had to take it off the market because it was found to increase the risk of bowel obstruction in infants. Opponents argued that it would take a large study and a huge investment of time and money to test Merck s candidate vaccine, and then to overcome public fears.

“Everyone wanted to kill it,” Dr. Gerberding said. “Adel said, Not only are we going to do it, but we re going to make our study even larger to prove it works and is safe. ”

Dr. Mahmoud took a similar approach to the HPV vaccine, which also had its detractors. Some doubted that it would work. Others thought parents would reject it, fearing that vaccinating young girls would somehow encourage them to start having sex. That fear was based on the virus s being sexually transmitted and the view that the vaccine was most effective if given before girls become sexually active.

23 Seconds, 5 Critical Moments: How Stephon Clark Was Killed by the Police

1,600 Degrees and Mass Destruction: Explore a Town a Volcano Made a Tomb

Dr. Mahmoud prevailed, and Merck s HPV vaccine, Gardasil, approved in 2006, was the first to be marketed.

Last month, in a call to eliminate cervical cancer worldwide, the head of the World Health Organization called HPV vaccines “truly wonderful inventions” and said all girls should be given them.

Dr. Adel Mahmoud, who joined the Princeton faculty after leaving Merck, taught a class at the university s Lewis Thomas Lab in 2008.CreditBrian Wilson/Princeton University, Office of Communications

Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said he had called on Dr. Mahmoud many times to advise his institute.

“He clearly had a knack for understanding the big picture,” Dr. Fauci said. “He was a 40,000-foot kind of guy, who could understand areas of science, research, policy and clinical medicine well beyond his own specific designated area of expertise.”

Dr. Mahmoud also had “an amazingly likable personality,” Dr. Fauci said.

“Even though he was dead serious when advising you on important matters, he had this effervescent, bubbling personality,” he added.

Adel Mahmoud was born on Aug. 24, 1941, in Cairo, the eldest of three children. His father, Abdelfattah Mahmoud, was an agricultural engineer. His mother, Fathia Osman, did not work outside the home, though she had hoped to study medicine and had been accepted by the University of Cairo s medical school. Her brother, a medical student, had stopped her from attending because he did not think women should be doctors.

A boyhood experience had a profound influence on Dr. Mahmoud. When he was 10, his father contracted pneumonia, and young Adel was sent to the drugstore for penicillin. He ran home with it only to find that his father had died. As the eldest son, he was now head of the family.

“I often wondered if his strength as a leader and his clear vision originated from being forced into those roles at an early age,” his wife, Dr. Hodder, said.

Dr. Mahmoud studied medicine at the University of Cairo, graduating in 1963. He left Egypt for Britain in 1968 and earned a doctorate from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in 1971. He did research on diseases caused by parasitic worms and the role of a certain type of blood cell in the body s efforts to defend itself.

Dr. Mahmoud emigrated to the United States in 1973 as a postdoctoral fellow at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. He later led the university s division of geographic medicine and was chairman of the department of medicine from 1987 to 1998.

He met Dr. Hodder there in 1976, and they married in 1993. She is also an infectious-disease specialist.

Merck recruited Dr. Mahmoud in 1998. He retired from the company in 2006, and then became a professor at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs and the department of molecular biology at Princeton University.

In 2013, when an unusual strain of meningitis caused an outbreak on campus — one for which there was no vaccine made in the United States — Dr. Mahmoud used his expertise, powers of persuasion and connections in the pharmaceutical world to help the university acquire a European vaccine and obtain permission from the government to offer it to students on an emergency basis.

After the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014, Dr. Mahmoud began advocating the creation of a global vaccine-development fund.

In addition to his wife, he is survived by a stepson, Jay Thornton; his sister, Dr. Olfat Abdelfattah; and his brother, Dr. Mahmoud Abdelfattah.