For seven decades, the equations of the Arab-Israeli conflict revolved around two variables: the creation of realties on the ground and political, diplomatic and military prowess.

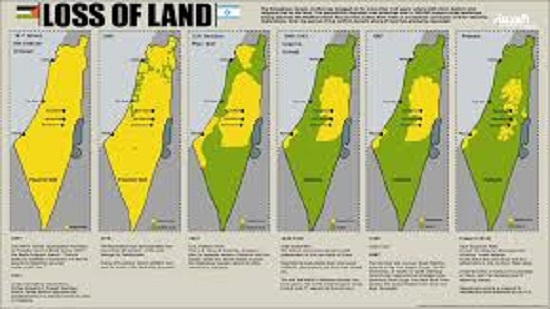

The result was the establishment of the atate of Israel, its expansion beyond the borders set by the 1948 UN partition resolution, and its subsequent expansion after the 1967 War to an empire extending from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean and from Qantara in Syria to Quneitra east of the Suez Canal in Egypt.

The Arabs only began to tip the scales in the other direction after the October 1973 War, which led to the shrinkage of the Israeli empire through the deduction of Sinai, parts of Jordan and bits of the Syrian Golan.

Meanwhile, the Palestinians have remained unable to realise their dream of an independent state. They have achieved a “national authority” on Palestinian land for the first time in history. But that authority is weak and limited in capacities and powers.

Also, while Israel has succeeded in gathering in a considerable portion of the Jewish diaspora, evolving into a technologically and militarily advanced country with worldwide influence, and retaining the ability to expand its settlements in the occupied territories, the conflict has not only hampered Arab progress and development, it has also generated extremist trends that are incompatible with both the Palestinian national movement and the world abroad.

Hamas rule is a far cry from what the founders of the Palestinian independence movement had in mind. Still, after 70 years, six million Palestinians hold their ground on the land of Palestine between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea.

Today, the foremost item on the regional discussion agenda is the new diplomatic round to resolve the Arab-Israeli conflict by means of the “Deal of the Century” that President Donald Trump had spoken of during his election campaign and after becoming president, and that is now being handled by his aide and son-in-law Jared Kushner.

Washington s new Middle East diplomatic effort comes in the framework of a massive drive to reorient US foreign policy. This began with the major deal struck between the US and North Korea and with steps to restructure US trade relations with the world (specifically with China, Europe, Japan and with its neighbours, Mexico and Canada).

Now, preparations are under way for a new deal with Russia, perhaps to be unveiled in the forthcoming summit in Helsinki on 16 July.

Therefore, the “Deal of the Century” is not a freestanding initiative; it is part of a new approach that Washington wants to cement, in order to make US leadership of the world order more cost effective and, perhaps, better, at least if striking deals can succeed where weapons cannot.

The Middle East deal departs from the principles for a two-state solution generally agreed upon by generations of diplomats.

It grants the Palestinians a state within the area currently under the control of the Palestinian Authority while the Israelis retain responsibility for and control over the security of the whole area between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean, while Jerusalem becomes the capital of the Hebrew state.

If this is much less than what the Palestinians want, the deal appears to offer more from the economic standpoint: the Americans have pledged to turn the Palestinian territories into a Middle Eastern “Singapore”.

Naturally, it is premature to determine how Palestinian and Arab governments will react to a deal the details of which remain secret. S

o far, however, Arab political and media circles have tended towards rejection and condemnation. Some have tended towards fabrication, such as that fiction of a land swap deal that would give a portion of the Egyptian Sinai to Gaza in exchange for an equal portion of the Negev to Egypt.

Still, sooner or later, something clearer will emerge on the regional political table. Note, in this regard, the many changes taking place in Iran, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Turkey, all of which make it necessary to reorder the cards related to the Arab-Israeli conflict and the Palestinian cause.

In other words, it would be wise to begin to think of the Arab reaction as of now, not in terms of how to handle the press, but rather in terms of an agreed upon approach or a “higher strategy” so that we will be better able to respond to initiatives and stances when the time comes.

The first point that should be taken into consideration when forging this approach or strategy is that the current status quo is unacceptable.

In addition to the strains on the Palestinian people under the siege and the expansion of Israeli settlements, there is the internal Palestinian polarisation between those able to accommodate to the occupation and those determined to sustain the armed struggle against it.

Changing the status quo, economically, will take more than a number of infrastructural changes such as building a port in Gaza and reopening the Gaza airport.

The siege must be lifted and the checkpoints and all other restrictions on the Palestinians freedom of movement in the West Bank and Gaza must be removed so that the Palestinians can enjoy the right to invest, build and engage in commercial activity everywhere in Palestine

Secondly, it should be borne in mind that the main point of negotiations, even before the establishment of the Palestinian state, is to ensure that Palestinians are able to survive, grow and prosper in Palestine.

The Palestinian-Israeli conflict has revolved around geographic realities such as the partition of the territory and Israeli expansion beyond set boundaries.

For more than a quarter of a century, negotiations essentially focused on the borders of the envisioned Palestinian state and the extent of Israeli territorial expansion.

As important as this is, it should not overshadow the demand for equality between Palestinians and Israelis in rights and duties wherever they coexist.

Discrimination in the right to build, whether between Jewish settlers and indigenous Palestinians in the West Bank or between Jews and Arabs in Jerusalem, is an unacceptable form of racism.

Thirdly, Arab states that are willing to support and contribute to the solution process are not prepared to do this by pressuring the Palestinians into accepting the unacceptable but, rather, by giving the Palestinians the resources to help them build a modern state in which the people are no less educated, skilled, healthy or wealthy than Israelis or even Palestinian citizens of Israel.

Any solution to the century-old conflict must be situated not in geography, where the conflict is “existential”, but in demography whereby people are equal in their capacities and resources and where competition becomes the basis for dealing with the conflict.

Current realities in the interplay between Palestinians and Israelis, whether in Israel, itself, where the Palestinians hold 13 seats in the Knesset, or between the West Bank and Israel with respect to labour, healthcare, trade and a single currency, have created a common market between the two sides. But it is not a fair market in terms of opportunities and rights.

Simply put, if economy is to be part of the solution that the “Deal of the Century” seeks, then it must be established on the foundations of a free market without discrimination and walls.