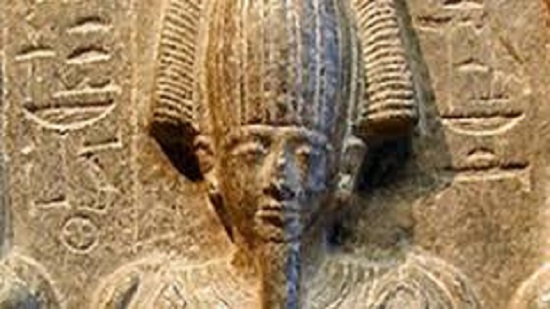

“The full court in all their divine regalia assembled in the Hall of Justice where towering walls of sacred glyphs soared to the ceiling far above, a shimmering golden sea of human dreams. Osiris presided on his golden throne. To his right sat Isis on her throne and to his left sat Horus on his. Thoth, the Scribe of the Gods, sat cross-legged a short distance away, the Book of All open on his lap. Ranged along either side of the great hall were rows of chairs, gilded in the purest gold, awaiting those destined for salvation. Since time immemorial, said Osiris, commencing the proceedings, it has been determined that the souls of humankind shall follow their bodies like a shadow through their days upon the earth, then pass beyond, across the threshold of death, bearing their deeds and intentions embossed on their naked shrouds. After great deliberation, it has been determined that this is the hour of truth and, thus, the court shall now convene for a lengthy journey. Osiris then nodded to the young Horus who announced in a sonorous boom: King Mena! ”

Before the throne

by Al Ahram

Opinion

00:03

Friday ,06 March 2020

In Naguib Mahfouz s novel, Before the Throne (1983), all the rulers of Egypt, from Mina to President Anwar Al-Sadat, were summoned before the great court to recount their deeds. The novel is long, intentionally so, because it covers millennia in the relationship between Egypt s rulers and their subjects and between Egypt and its neighbours. Egyptian history has brought rulers to account for 5,000 years. The “Osirian” faith prevailed during 3,000 years of this history, Christianity for several centuries and then Islam for the many centuries since the Arab Muslim conquest. But the court was not interested in a ruler s religion but rather in the fact that he was an Egyptian who lived his whole life in Egypt and dedicated himself faithfully and courageously to protecting the Egyptian people and their welfare. The ancient Egyptian faith had the magnanimity to accept diversity in the religions that accepted monotheism and were grounded in nobility of conscience. If the verdicts passed on the pharaohs of the Old, Middle and Late Pharaonic kingdoms harked back to “Osirian” laws, since Muqawqis came to Egypt the judgements were based on the recommendations handed down by an imagined court of a later faith.

The court could issue three types of verdicts: the ruler could be granted immortality and join the court, he could be pronounced guilty and condemned to a hellish afterlife, or he could be sent to the tomb of “the inconsequentials”. Many rulers were admitted to the ranks of the immortals. Either their accounts of their glories and services to the country and its people spoke for themselves, or Isis intervened, citing the testimony of one of her children and pleading sympathy for the ordeal the ruler endured in his struggle to do what was right. Naturally, she had no mercy for those who rebelled and betrayed her trust. After Sadat is admitted to the immortals in Before the Throne, Isis addresses them: “Let each of you pray to his god to bestow on Egypt the wisdom and strength to remain an eternal beacon of guidance and beauty,” after which all allowed to remain in the great hall bowed their heads in prayer.

The novel bears all the hallmarks of Naguib Mahfouz s art. But we re not here to discuss the craft of this Nobel laureate or literature in general, but rather the political element in this work and, specifically, politicians in power. Its subject is the Egyptian state from antiquity to modern times. At the moment of the trial of Sadat, it brings all Egyptian leaders into the court, whether known for their might, their justice or their advocacy of integrity. Naturally, Mina, Tutankhamen and Ramses II are present. So too are Saad Zaghloul and Mustafa Al-Nahhas. Gamal Abdel-Nasser defends his place among the immortals and expresses his dismay at what came after him. This is not the only Mahfouz novel that draws comparisons between Egypt s rulers. In Qushtumur (The Coffeehouse), coffeehouse denizens have their say and Akhenaten, Dweller in the Truth speaks of relations between power and the people, a subject that is given a different treatment in Children of Gebalawi and Harafish where power turns more concrete or metaphysical.

Mohamed Hosni Mubarak had been in power for some time when Before the Throne appeared in bookstores. He would leave power three decades later, in 2011. Those 30 years placed him alongside Ramses II and Mohamed Ali in terms of longevity as head-of-state, but he is the only Egyptian leader to endure nine years of actual trials after leaving power.

Mubarak had many honourable virtues, not least the military ones. He was a model Egyptian soldier: courageous, capable, patriotic, self-sacrificing. He served in active combat, as a pilot in 1956, 1967 and 1968-1970, and as an air force commander in the October 1973 War. After that, Sadat chose him from among all other military commanders to serve as his vice president, during which period he trained in diplomacy, politics and political sagacity. While Mubarak, after coming to power, remained committed to implementing the peace agreements with Israel, he refused to give the Israelis room for evasion. When Taba came under contention, he did not hesitate to fight the complex and critical arbitration battle to the end. He won. Not a single centimetre of Egyptian territory remained under occupation. But Mubarak did not eliminate war as a political option. His courageous decision to participate in the war to liberate Kuwait reflected a transformation in Egyptian relations with the Gulf states. Not only had Egypt proven itself a reliable partner in war, it had acquired the diplomatic clout to serve as a mediator in the Khufous crisis between Saudi Arabia and Qatar. This was consistent with an important tenet in Egyptian strategy: Egyptian-Gulf relations needed to be strong in the face of regional and international challenges.

As Mubarak stands “before the throne” he will also be able to offer abundant evidence of infrastructural development in a country in which infrastructure had deteriorated to the point of near collapse during the two decades since the June 1967, when development ground to a halt. Most likely, he will also explain his economic policies which, after a period of wavering, settled on the need for economic structural reform, which included shifting the geo-economic keel outward from the eternal Nile through the deserts to the shores of the Red Sea and Mediterranean.

Naturally, he had his flaws. He hesitated too long before resolving on reform and, when he did, he was perhaps too cautious, which left many gaps in the economy. These were exploited by “money management firms” and the Muslim Brotherhood who ran them as they leveraged themselves back into politics behind the facade of the Wafd Party or the Labour Party. All this created a brew in which terrorism could and did rear its head. However, Mubarak ultimately prevailed in the round of the 1990s, making it possible to set Egypt on course to serious reform. The revolution came anyway, and now historians will have their say. But there is no doubt that Mubarak was true to his word, an Egyptian to the core, and a patriot devoted to serving his nation and its people. May he rest in peace.