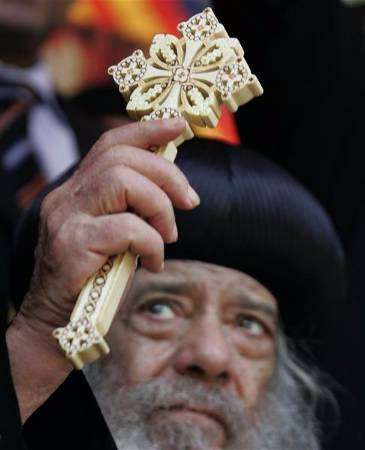

Under the gilded chandeliers of the grand Pharaonic Hall in the Egyptian parliament, heavily-bearded Islamists drink tea and exchange hearty greetings with a handful of secular politicians and a priest from the Coptic Christian minority.

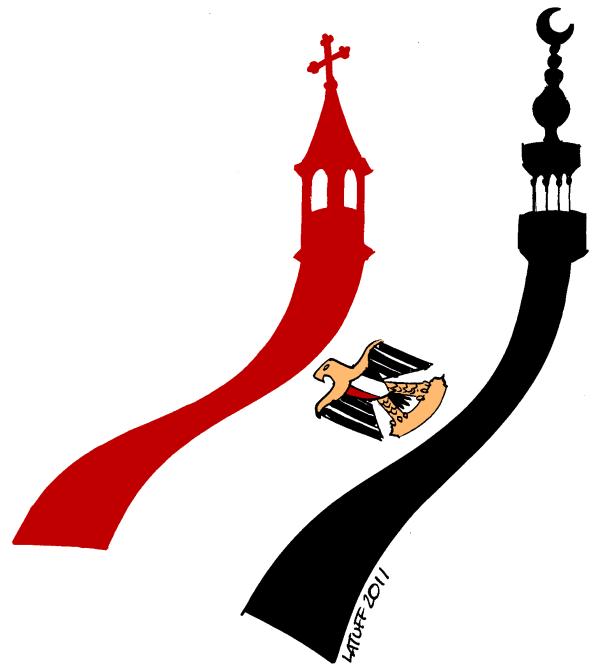

This is the new Egypt: a 100-member group from across the political spectrum coming together to help draft a constitution that will underpin the country’s future as a democracy.

But the cordial atmosphere belies the deep divisions within the group, formally known as the constituent assembly, over how that future will look. Huge differences persist between Islamists and liberals over the basic nature of the state that is being mapped out in the new charter. Islam, and the degree to which it will govern both public and private life, is at the heart of the disagreements.

Inside the panelled chamber where the discussions are held, the arguments highlight the starkly divergent visions held by each side, as well as the radical shifts in society that could be in prospect if more hardline Islamists on the panel have their way.

Chief among them is whether the source of sovereignty in the new Egypt should come from “the people” – the conventional formulation in most democracies – or from God, as proposed by the ultraconservative Salafists.

Farouk Guweida, one of Egypt’s foremost poets, rises to protest. “This is not something that should be proposed or even discussed,” says Mr Guweida. “God does not need any of us to give him sovereignty.”

But Nader Bakkar, an official of the Salafist Nour party, quickly makes an impassioned retort. “To say that sovereignty belongs to God is an affirmation of the beliefs of the Egyptian people, which differ from the convictions of other nations who hold that the people have an absolute right to legislate for themselves without being bound by religion,” he says.

The Nour party garnered almost a quarter of the vote in parliamentary elections earlier this year, surprising most observers, and is demanding strict adherence to its vision of an Islamic society. Its members are trying to pre-empt the possibility that any future parliament could push through a law that breaches their interpretation of Islam.

They have been leading a campaign to stiffen the wording of an article that says sharia, or Islamic law, should be the source of legislation. Previous Egyptian constitutions have enshrined the principles of sharia law as “the main source of legislation”, but the courts have interpreted this to mean that laws should conform to vague principles, such as justice and equality.

For the Salafis this is not enough. If they cannot change the wording of the article, they propose that clerics from al-Azhar, Sunni Islam’s most venerable theological centre, should be constitutionally charged with vetting laws to decide if they are sharia-compliant – a notion that horrifies liberals.

“Giving Azhar this role would immediately mean a theocratic state,” says Wahid Abdel Meguid, a political analyst who is also a member of the panel. “This takes us to medieval Europe or 20th century Iran. It is a radical change that would be a danger to both religion and the state.”

How the issue is resolved will depend on the position of assembly members from the Muslim Brotherhood group of Mohamed Morsi, the country’s first democratically elected president.

The Brotherhood is the largest political force in Egypt, and the largest grouping on the assembly, but has been accused by liberals of manoeuvring to ensure that Islamists form the majority. For this reason many liberals pulled out of the grouping in June, soon after it was formed.

The assembly also faces a legal challenge, which could see it dissolved by court order later this month, although Mr Morsi has the right to appoint a replacement and is not expected to change its composition.

“There is certainly a battle over the relationship between religion and the state,” says Mr Abdel Meguid. “So far the Brotherhood has maintained an ambiguous position which we interpret negatively. If they do not make their position clear and definite and the Salafis insist on a radical change, the remaining democratic forces in the assembly will not be able to continue.”

Although voting rules on the panel require only a 57 per cent majority for articles to be adopted – another sore point for the liberals, who wanted a larger majority in the interests of consensus – Mr Abdel Meguid says it will be an embarrassing failure for the Islamists if other groups do not support the draft charter.

Farid Ismail, a Brotherhood panel member, insists there is already agreement over 95 per cent of the charter, and he expects a consensus to emerge and the complete draft to be ready by next month.

“Our position is that we will contact all sides to find a consensus solution that satisfies everyone, including public opinion and the general Egyptian mood, which is currently leaning towards religion,” he says.