Like many of my compatriots, I aspired that after the elimination of Mubarak and his constitution there would be an honest and sophisticated debate about the constitution that would outline the principles and fundamentals that must be the foundation for the existence and continuation of the Egyptian people.

While I only dreamed of a sophisticated debate about the constitution, I never went as far as fantasising that Egypt’s post-revolution constitution would be similar to those of democratic states in terms of respecting the intellectual, creative, religious and socio-economic rights of citizens.

Egyptian society is dominated by currents that are psychopathically terrified of freedom, dismissive or uninterested in championing those who are victimised for religious, economic or social reasons. I held back my dreams and limited them to the debate on the constitution rather than the constitution itself to avoid disappointment, but that did not work. I am already disillusioned and disheartened because the debate on the constitution in recent months often ignored discussing sensitive and core issues. It has also been hasty and fraught with disputes about the legitimacy of the Constituent Assembly in charge of drafting the constitution.

What is even more frustrating is how far ahead Tunisia is compared to Egypt. I surfed many Tunisian websites to read their draft resolution and tune into their discussions of it. As expected, I found them more advanced than us in terms of substance as well as calibre of debate.

Their constitution clearly adopts the principle of equality between men and women; ours is reticent and contradictory on the issue. Ours, in fact, mostly only remembers Sharia when women are mentioned, to restrain her rights and freedoms, but forgets Sharia altogether in placing any restrictions on men.

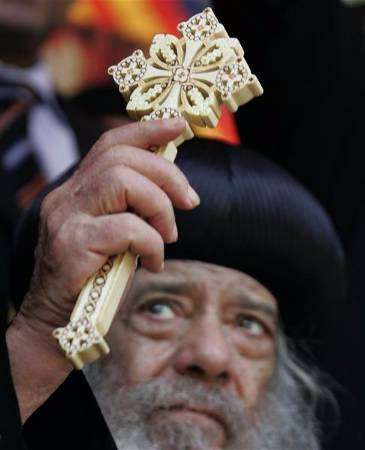

Tunisia’s constitution is very precise about accepting religious freedoms, while ours grants them with one hand and takes them away with the other. It recognises the freedom of belief but does not allow the proclamation of this belief or practicing its rituals unless it is one of the three “divine” religions. This, of course, is a flagrant lie because the majority of Muslims view Egyptian Christians or any other Christians around the world as practicing distorted and incorrect versions of the ancient divine Christian faith. Meanwhile, Christians in Egypt do not recognise the divinity of the Muslim faith.

These are a few observations about the substance of the Egyptian and Tunisian constitutions.

As for the debate in each country, theirs has reached a wide spectrum of the citizenry while ours is limited to a small segment of politicians, media and public figures. This comes as no surprise since the level of education in Egypt is lower than in Tunisia, and the steps taken by former Tunisian President Al-Habib Borqeba to orient the state towards secularism were so extensive that it is difficult to reverse many of the gains.

The issue of women’s rights in Tunisia is not a matter of rights women are trying to obtain today, but is the legacy of three or four generations of women who exercised these rights. Therefore it would be difficult for anyone to take them away from them today. This is why conservative currents there are more cautious than their counterparts here in assailing women’s rights.

We must not only insist on a minimum level of our aspirations; we must also assert our right and duty to have an honest and civilised debate about the provisions of the new constitution, because these discussions are a golden opportunity to talk about the principles and fundamentals of issues.

We do not know the fate of the Constituent Assembly that wrote the draft constitution, but this should not let us slacken in discussing the substance of the constitution itself.

Let disputes continue about those writing Egypt’s constitution, but in parallel we must launch discussions about basic definitions and core issues of the constitution. We must ask its authors about the meaning of every letter they wrote; we should ask them to define the state they often mention in the draft without bothering to once define it. We should ask them about the definition of the word republic; we should ask them about the phrase "rulings of Islamic Sharia."

Here, we must also note that the draft constitution (unlike the Tunisian one) does not include a preamble or introduction. Have you ever heard of a book without a prologue? Can you ever connect to a book without an introduction, or the writer describing what you are about to read?

The preamble to a constitution is no less important than the provisions of the constitution themselves, because it frames the constitution in its historic context and reveals the governing logic of the constitution’s provisions.

I fantasised that Egypt’s wordsmiths of the calibre of Bahaa Taher would be in charge of writing the preamble to the constitution, but not only were the literary virtuosos of our country not invited to write the preamble, the constitution was “rushed” without an introduction. Where is the preamble, oh authors of Egypt’s draft constitution?