Egypt 2020

The second decade of the 21st century showed little mercy for Egypt, its Middle Eastern environment and the world. It opened with the tumultuous events called the “Arab Spring”. Egypt s share of this “season” was the January 2011 and June 2013 Revolutions, in between and after which development ground to a halt, infrastructure deteriorated, and terrorist groups were spurred into action under Muslim Brotherhood rule and remained a severe threat that only began to subside as this decade drew to a close.

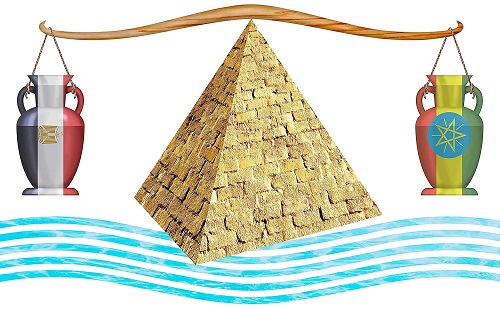

Elsewhere in the region, “revolutions” led to civil wars and intensive foreign intervention. In the process, oil prices soared and then plummeted, rocking the Egyptian economy in both cases. Regional powers, such as Iran, Turkey and Israel, grew more aggressive in their interventions and expansionist designs, while the Palestinian cause encountered major setbacks. Ethiopia grew less cooperative in the management of Nile waters and initiated construction of its Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.

The world as a whole was not much better off. The influence of international organisations and multilateral agreements waned as nationalist trends gained ground over pro-globalisation outlooks. Xenophobic ultra-right movements proliferated as they fed on and furthered racist stereotypes of Arabs and Muslims as religious fanatics, terrorists and illegal migrants. Meanwhile, the trade war between the US and China and political rivalry between the US and Russia hampered global economic growth and undermined the efficacy of the UN and other international organisations.

Nevertheless, the halfway point in this decade brought some positive developments in the form of sweeping reform drives in Egypt and other Arab countries in response to difficult challenges in the region. As we cross the threshold into this century s third decade, the cumulative changes of the second will carry with them Egyptian and Saudi developmental visions that were formulated in 2015 with their sights set on 2030.

In a study published in the November 2019 edition of The Egyptian File, published by Al-Ahram Centre for Political and Strategic Studies, Hoda Youssef, an economic researcher for the World Bank, described the state of the Egyptian economy at the end of this decade as follows: “Although the economic reform programme that the Egyptian government initiated in 2016 in collaboration with the IMF succeeded in achieving stability and boosting confidence in the economy, it had negative social and economic impacts. While the targeted social protection measures that were taken to counter these impacts managed to alleviate the effects on some of the targeted sectors of society, the measures were inherently limited and restricted to their range of coverage. In addition, they failed to address the harm the middle class suffered due to the erosion of its real income levels.

It is therefore necessary to proceed to the second generation of reforms which focus on structural problems, remedy the foundations of the economy and clear the way for private sector participation so that the improvement can be felt positively and tangibly across all social classes, age groups and professional categories, as well as across all geographical areas. This entails unleashing Egypt s export potentials as a basic engine of growth, and establishing rules for competition and equal opportunity for businesses in a manner that ensures that rules apply equitably to all companies, regardless of whether they are owned by the private or public sector. Above all, it is essential to invest in human capital which is the sine qua non for the efficacy of all other reform processes.”

Actually, Egypt accomplished much more during the second half of the outgoing decade. It succeeded, firstly, in routing terrorism, and secondly, in building an extensive infrastructure linking the Nile to Egypt s Red Sea and Mediterranean coasts through a network of roads and transportation facilities. It followed through on a moderate foreign policy based on upholding the peace with Israel, resolving Egyptian-Ethiopian differences through peaceful means, working to promote regional stability and forging a large network of cooperative relations with other Arab countries focused on the regional and international benefits to be had from serving the processes of domestic development in Egypt.

In this framework, the delineation of maritime borders between Egypt and Saudi Arabia has cleared the way for the development of the Red Sea region and Sinai. In like manner, the maritime borders agreement between Egypt and Cyprus has made it possible to exploit offshore oil and gas resources and to found the Easter Mediterranean Gas Forum which regulates the processes of natural gas production, liquidation and use in Egyptian industries.

Egypt will also enter the third decade of the 21st century with its balance of trade tipping in favour of exports and the highest growth rates in the Arab region and Africa, a trend that is expected to continue during the coming decade due to the newfound wealth of fossil energy resources on top of growing renewable energy resources. Egypt will also enter the next decade spurred not only by the upswing in exports but also by other drivers of nationwide development: encouraging the capital accumulation needed for 100 million Egyptians; stimulating the human resource factor through education, health and culture; advancing the legislative revolution needed to ensure Egypt s advancement on the ladder of business practices; and restructuring the Egyptian administrative map to enable “decentralisation” and “local government” to take the lead in driving investment and mobilising local and national resources.

This Egyptian dynamism at the turn of the third decade of the 21st century will face difficult domestic challenges and just as difficult external challenges. Egypt will be crossing the decade threshold with a population that has crossed the 100 million mark (of which 10 million live abroad). It is expected to climb another 20 million by 2030. This population is afflicted by three harsh realities. Some 32.5 per cent of it are poor, 26 per cent are illiterate and there is a sharp economic growth disparity between northern and southern Egypt. To address this triple challenge, the current economic growth rate of around 5.6 per cent will need to rise to eight per cent. The dilemma, here, is that economic growth frequently brings inflationary pressures which affect the middle class which, in turn, requires remedies to safeguard against the political consequences.

With regard to external challenges, firstly, the countries that have been the most violently shaken by the Arab Spring revolutions remain weak, weary, fragmented and plagued by chronic instability. Iraq and Syria stand out foremost in this regard. As a result, they are likely to remain vulnerable to further Iranian, Turkish and Israeli interventions. Secondly, although the Egyptian-Ethiopian water crisis that persisted throughout the outgoing decade appears likely to be resolved, the 2020s may usher in quite a number of other crises due to Israel s undermining of all opportunities for a peaceful settlement to the Palestinian cause, Iranian revolutionary expansionism in the Gulf region and Turkish designs in the Levant. Thirdly, the possibility of war between Iran and the US, due to the collapse of the 2015 Iranian nuclear agreement, could precipitate a larger war in the region.

The global environment will continue to pose equally tough if not tougher challenges to Egypt in the coming decade. As a consequence of global warming, there has emerged a rival to the Suez Canal in the Artic Circle. While the construction of the second Suez Canal and the development of the Suez Canal Corridor give Egypt a competitive edge, the repercussions of climate change, apart from the damage they inflict in Egypt, will affect the levels of international trade that passes through Suez. Secondly, although the ongoing US-Chinese trade war has abated somewhat as we enter the new decade, it could resurge, especially in light of the decline in the European role following Britain s exit from the EU and the repercussions of Brexit. No less demanding a challenge will come from the increasingly fast-paced changes in global technologies related the fourth industrial revolution.

Egyptian economic capacities and its international economic standing will come under heavy pressures unless Egypt takes quick action to catch up and keep pace with the technologies required to enhance its competitiveness. Lastly, the surge of “identity” politics, the rise of extremist and ultranationalist trends and the decline in the role of international organisations and multilateral agreements will make the world that Egypt has to deal with in the next decade more difficult, complex and puzzling.

This said, Egypt has just emerged from the difficult and complex circumstances of the outgoing decade with its head held high. Armed with the abovementioned drivers and resolve, Egypt will be much better poised to deal with the new challenges.