Will Europe pay its debts to Africa?

Human rights are based on the principal of equality, meaning “all rights to all people”. They also infer equality between countries, all of which have equal rights and duties towards their people and other countries.

When Europeans invaded Africa, they found people who are different in looks, colour, creed and with different values and traditions. They assumed these are not “humans” and decided to own their land and resources. The record of Europe in Africa is not very honourable. With European countries competing to control Africa, the UK was the “pioneer”, and now that Europe is advocating equality and “human rights” all over the world, I am confident that they are now willing to correct their behaviour and pay their debts to Africa.

PIONEER OF THE INVADERS: France and Portugal had started their exploits in Africa. Britain had conquered southern Africa and penetrated parts of the western coasts of the continent. These incursions were met with resistance prompting the British parliament in 1854 to ask the government to stop its campaigns in Africa. Until 1875, the size of the British possessions in Africa did not exceed 640,000 square kilometres, some of which had been purchased from Denmark and some had been exchanged with Holland against lands in Sumatra and Southeast Asia. Britain also exercised strong influence in Zanzibar which had been separated from Muscat by the governor of India in 1861.

France, meanwhile, appropriated a small part of the North African coast in Algiers, Senegal, Guinea coast, the Gulf of Gabon and some areas on the southern coast of the Red Sea. The Portuguese had appropriated land that did not exceed 100,000 square kilometres. In the 1870s, the European powers were involved in heated competition to conquer and divide the African continent among themselves.

Germany joined the race after its victory in the 1870 war with France. At the same time, France began settling and colonising parts of north Africa. Italy went into Eritrea. The king of Belgium, who was intrigued by the discoveries of Livingstone and Stanley in the Congo Basin, decided to send an expedition to occupy that basin. The success of the expedition aroused the concern of the European powers who feared that this might encourage individual adventurers. This led them to expedite the apportionment of the African continent among themselves.

For years after that Africa became the scene of intrigue and military exploits. Portugal occupied Angola and Mozambique, Germany occupied Tanganyika and Cameroon, and Britain the Niger Basin and then the Nile Basin.

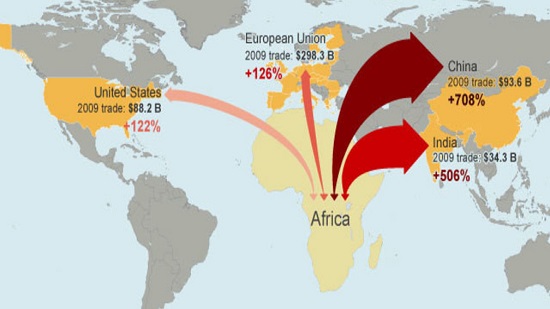

The US contributed to the invasion of Africa, not as an occupier but as an enslaver. Africa was the source of slaves who build that emergent nation, and they only obtained their freedom after a gruelling civil war.

All the countries above, without exception, exploited Africa, abused its resources and exploited its people. Even the River Nile, the pure and eternal African wonder of the world, they considered their own.

In November 1884, the colonial powers met at a conference in Berlin to determine and outline their spheres of influence in Africa. The conference was attended by Germany, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Spain, the United States, France, Britain, Italy, Holland, Portugal, Russia, Sweden, Norway and Turkey. In a series of acts, protocols, agreements, treaties, declarations and exchanges of notes, collected in three volumes by Hertslet (1967), participant powers delineated their spheres of influence, which eventually became the borders of modern African states as we know them today.

Foremost among these agreements are: the Rome Protocol, 15 April 1891; the Addis Ababa Convention, 15 May 1902; the London Convention of 13 December 1906; the Rome Convention of 1925; and the July 1993 Cooperation Framework. Two agreements between Egypt and Sudan were struck in parallel: the 1929 Convention; and the 1959 Convention.

THE COLONIAL RESOURCE-GRAB: Africa does not need European resources. The reverse is the case. Africa has vast stretches of cultivable land and it has agronomists and other scientists who work in international organisations and Western nations. It is rich in basic minerals. There are abundant sources of iron in Mauritania and Zambia, of aluminium in Guinea, nickel in Mozambique, chrome in West Africa and natural gas in Egypt.

But Africa does need two things: the transfer of the technology and knowhow to enable African countries to optimise the utilisation of their resources, especially in such fields as healthcare, fighting epidemics, education, modernisation of agriculture, industrialisation and exports; and investment, in particular in order to support infrastructural development, an area in which Egyptian expertise can contribute greatly.

Egypt, as chair of the African Union, underscored these realities and drew up the necessary plans for the development of the African continent and its people. It convened numerous conferences and meetings towards these ends, the most recent of which was the third G20 Africa Summit in Berlin to bolster the business climate and spur investment in the continent.

WHERE EUROPE CAN MAKE AMENDS: One of the foremost areas in which Europe and Africa can and should work closely together is water resources. Africa, like other regions in the world, is grappling with the problem of both the availability and quality of fresh water. The continent s needs in this regard call for numerous hydraulic projects to harness water for electricity (such as the electricity generating project that Egypt has been working on in Tanzania), to put cultivable land to work, to prevent water loss due to evaporation, to make potable water available to millions and to serve other crucial developmental needs.

The Bahr Al-Ghazal, the main western tributary of the Nile, is an area that merits closer attention due to the huge amounts of water that are lost in the vast marshes known as the Sudd wetlands. It is a region that offers plenty of scope for canalisation and other hydraulic projects to conserve and harness the lost water.

Another area where enormous amounts of water are lost is at the source of the White Nile in the Great African Lakes. The Lake Victoria basin receives more than 110 million m3 a year, but only about 30 million m3 of this exits the lake into the White Nile. Only 33 million m3 of water makes its way through the White Nile from the Equatorial plateau into the approximately 700 km2 of Sudd wetlands. It is here in this region where the Bahr Al-Ghazal, which flows 160 kilometres eastward from Al-Riqq, joins the White Nile at Lake No. Only six per cent of the more than 500 million m3 of rain that falls on the Bahr Al-Ghazal basin makes its way into Lake No.

Surely hydraulic projects in these areas would offer an excellent opportunity for Nile Basin countries to overcome longstanding differences between upstream and downstream countries (Egypt and Sudan) by working together to persuade Europe to fund much needed water conservation projects. Perhaps Lake Victoria could be the starting point, it being the largest of the African Great Lakes (69,000 km2) and the main source of the White Nile.

There has been a proposal to construct a dam to help conserve the waters lost from this lake. This could be the focus of a cooperative project that brings together Nile Basin countries and Europe in an endeavour that could greatly augment available water resources in the White Nile, which would be shared equitably in accordance with an international agreement.

I know that such an idea has been mooted before, but it never got off the ground because of a number of conflicts of interests and ambitions. However, President Abdel-Fattah Al-Sisi, who has the resolve and discernment to rise above petty differences and look towards the future, has ushered in a new phase for Africa based on mutual understanding and cooperation, and it is this spirit that should encourage the governments concerned to re-examine their positions for the sake of the collective benefit to be had from preventing the loss of enormous quantities of Nile waters.

PAYING COLONIAL DEBTS: For centuries, European countries colonised, exploited and enslaved the peoples of Africa. Today, they should repent, by which we mean they should remedy their wrongs by contributing to the development of this continent.

There is plenty of scope for this through any number of development projects to which Africa s European partners could contribute. They should simultaneously bear in mind that they, too, stand to gain, as development of Africa is the key to stemming the flows of migrants escaping prevailing hardship and strife in Africa.

The key to success here is European political will combined with a convergence of opinion among the African countries concerned. Fortunately, Egypt s chairmanship of the African Union has worked to raise international awareness, mobilise global public opinion and alert international organisations and European governments to their responsibilities. The question now is whether Europe will pay its debts to Africa.