In the run-up to talks with Iran last month, many in Europe and the United States asked whether Iran would, or even could, come clean on its nuclear activities.

In the run-up to talks with Iran last month, many in Europe and the United States asked whether Iran would, or even could, come clean on its nuclear activities.Should the West trust Iranian promises? The short answer is "no." But the underlying question is "Why not?"

The answer lies in Iranian belief systems – notably the doctrine of taqiyya, a difficult concept for many non-Muslims to grasp. Taqiyya is the Shiite religious rationale for concealment or dissimulation in political or worldly affairs. At one level it means that President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and his regime can tell themselves that they are obliged by their faith not to tell the truth.

This doctrine has not been discussed much in the West, but it should be. How should the world deal with taqiyya in Shiite Islam in the context of Iran's nuclear file?

CAN IRAN BE TRUSTED?

In Iran, the teachings of Shiite Islam govern all aspects of society. And taqiyya – dissimulation and concealment – is one of the key elements of the Shiite faith. While many outsiders are surprised by Iran's concealment of its nuclear installations, those who study the Shiite faith and recognize the signs of taqiyya are not.

Many governments lie about strategic secrets, especially secrets about nuclear weapons. Witness Israel's concealment of its nuclear capabilities. And former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping counseled his country to "hide its brightness" – for strategic reasons.

Iran's approach to its nuclear ambitions, however, is a different form of deception and denial. Certainly states do not need a religious edict to lie or obfuscate. But it helps if a state has one already in place.

WHAT CAN THE WEST DO?

Western negotiators must be mindful, not only of the technical side of Iran's nuclear program, but the historical evolution of taqiyya. Such context sheds critical light on the insecurities of the Iranian regime and that of the Shiite community at large.

Taqiyya doesn't mean the West should give up all negotiations with Iran, or that Iran can never be trusted. Tehran's concealment is a means to an end: It wants nuclear weapons to provide security for the clerical regime and the Shiite community. So long as Iran feels threatened, it will deceive. But if the West can ease Tehran's anxiety with strong assurances, then negotiations will be more truthful.

HOW A DOCTRINE OF DECEIT DEVELOPED

Taqiyya requires the faithful to be deceitful at times of weakness. The history of Shiites in their conflict with Sunnis is a history of the downtrodden. They have been the underdogs in Islamic history, and have had to protect both their communities and their faith from being overrun by the more numerous Sunnis. Taqiyya emerged as a response.

Taqiyya offers a license to violate the strict rules of the faith in cases of extreme pressure or threat of extinction – something not unusual in Sunni-Shiite history. The doctrine allows dissimulation in the service of self-preservation, practiced by the faithful.

The teachings of Jafar al-Sadiq, the sixth Shiite imam, emphasise taqiyya as a political tool. "Befriend people on the surface, and keep your grudges and intentions hidden," he advised. He also defined the relationship between the Shiite and other Muslims: "[B]eing double-faced with one's own takes one outside the bounds of faith, but with others [with non-Shiites] is a form of worship."

The words of Shiite imams are viewed as having the authority of the prophet Muhammad, and they entail obligations. Taqiyya is one component of the faith, and the Shiites are instructed to practice it until the time the Mahdi returns. The Mahdi is the figure who, like the Messiah in Christianity, will return and spread justice on earth.

Until that moment occurs, the Shiite faithful are obliged to practice taqiyya in their dealings with other Muslims, as well as with non-Muslims.

OPPOSING VALUE SYSTEMS

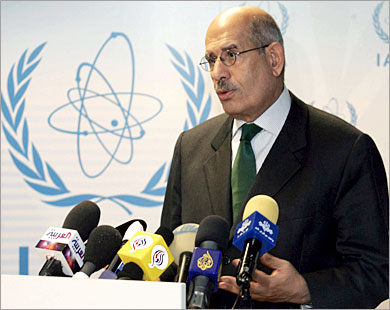

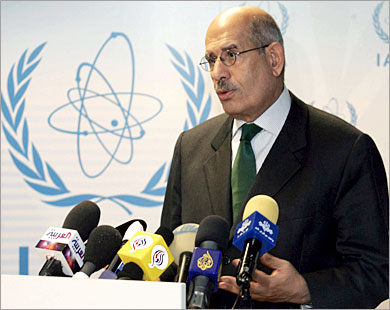

While the policies of the West and of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) are driven by the concept of transparency as a key doctrine of modernity and modern states, those who are negotiating with Iran must question the extent to which the Shiite regime in Tehran is driven by the concept of concealment. There are two different value systems at work here, making common ground exceedingly difficult to find.

Today the West may rightly be obsessed with nuclear installations in Iran, or the number of centrifuges it has, or even uranium-enrichment levels.

Last month, Iranian officials allowed IAEA officials to inspect a nuclear facility near the city of Qom. But they won't reveal everything: that would violate their faith. Shiites are obliged by their religious teachings to protect both the faith and the community until the return of the Mahdi. From Tehran's perspective, "nuclear" taqiyya is a must, because strategic nuclear weapons are the only means to protect the Shiite community in these modern times.

The West must understand that Iran's nuclear guile is a function of regime insecurities. And its insecurity is rooted in reality: Iran feels squeezed by the tens of thousands of US troops who brought regime change to its west, in Iraq, and to its east, in Afghanistan.

If Washington wants a breakthrough in its negotiations with Iran, it should make fewer threats and more assurances. Only when the Iranian regime feels safe will it negotiate in good faith.