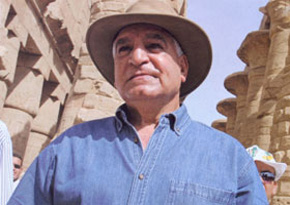

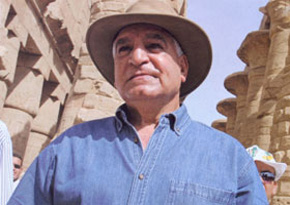

Head of Egyptian antiquities department Zahi Hawass promotes Egypt’s cultural treasures with a showman’s skills and an entrepreneur’s instincts, according to Bloomberg

Head of Egyptian antiquities department Zahi Hawass promotes Egypt’s cultural treasures with a showman’s skills and an entrepreneur’s instincts, according to Bloomberg

His Indiana Jones-style hat and vest and television- documentary appearances put an Egyptian face on Egyptology after two centuries of foreign domination, he says.

His goals include recovering icons such as a 3,300-year-old bust of Queen Nefertiti from abroad and restoring national pride in Egypt’s relics -- even in someone else’s museum.

“These artifacts remind us we were once a superpower,” he said during a Jan. 20 interview in his Cairo office.

Hawass’s approach is turning those artifacts into income for Egypt. Exhibits from Tutankhamun’s tomb that have traveled the U.S., Canada and Europe since 2005 were mounted in collaboration with National Geographic in Washington and Los Angeles-based AEG, owner of concert halls, sports teams and arenas. The tours have netted Egypt $100 million, Hawass said.

The partnerships represent a break from the past, when Egypt’s government paid to send treasures abroad on missions of national prestige.

“If I had managed the old exhibits, Egypt would be rolling in money,” he said.

Commercialization helps fund preservation of domestic monuments, construction of new museums and protection of sites. Tourism was the country’s top source of foreign exchange in the fiscal year through last June, bringing in $10.5 billion, and accounted for $3.2 billion during the first quarter of the 2010 fiscal year, three times as much as the Suez Canal.

Hawass’s Egypt-first focus underpins the celebrity and controversy surrounding him. He is unapologetic about his TV exploits: taking King Tut’s mummy into the open air in 2005 for a CT scan and declaring the discovery of Queen Hatshepsut’s mummy based on a missing tooth.

“A little publicity is a good thing,” he told a reporter when a wind blew up during the King Tut exhumation, feeding the legends of a mummy’s curse.

“This was just show business,” said Saleh Bedeir, a researcher who resigned from the scientific team of Hawass’s Supreme Council of Antiquities after the Tut project. “It has nothing to do with science.”

Hawass, 62, links Egyptology to refurbishing his country’s identity. Last month, he announced that a cemetery near the Giza Great Pyramids contained Egyptian workers who built the stone structures, not Hebrews toiling under the pharaoh’s whip.

“These people were not by any means slaves,” he said.

He has renovated Cairo synagogues to help persuade Egyptians of the value of diversity, he said.

“Our history is a unique blend: Muslim, Christian, Jewish, Arab. I want people to feel that.”

Hawass undermined such liberal pronouncements last year with comments about Jews on an Egyptian television talk show.

“They always move together, even if in the wrong direction,” he said. “Look at the control they have over America and the media.”

After his remarks made the Internet rounds abroad, Hawass said on his own blog he was only trying “to make a point about disunity and fighting in the Arab world.”

He was also criticized last October by the Cairo-based Arabic Network for Human Rights Information, which said Hawass was persecuting a researcher for disagreeing with him on how to handle mummies. The group said in a report that Hawass’s actions were “inhibiting scientific views.”

The Supreme Council issued a denial: “There is no truth to these arguments that we are attempting to curtail discussion.”

Repatriation may be Hawass’s most difficult campaign. The Nefertiti bust in Berlin’s Neues Museum and the Rosetta Stone in London’s British Museum top his wish list.

“There’s no legal basis, we have no legal right to get them back,” Hawass said. Yet he will persevere: “These are Egyptian monuments. I will make life miserable for anyone who keeps them.”

Victoria Benjamin, a spokeswoman for the British Museum, said in an e-mail the “trustees feel strongly that the collection must remain as a whole.”

Friederike Seyfried, director of the Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection at the Neues Museum, told Deutsche Presse Agentur Dec. 21, “the position of the German side is clear and unambiguous: The acquisition of the bust by the Prussian state was legal.”

Hawass banned France from exploration in Egypt last October to get the Louvre Museum in Paris to return frescoes removed in the 1980s. The Louvre complied because “serious doubts” emerged about “the legality of their exit from Egyptian territory,” France’s Culture Ministry said at the time.

Several international conventions since 1954 have prohibited wartime looting, theft and resale of artifacts. The bans don’t apply to the distant past, Hawass said.

He plans to hold a conference in April on the subject and invited 30 countries, including Greece, which wants the British Museum to return the Elgin Marbles, sculptures removed from the Parthenon in the early 19th century with permission of Ottoman rulers; and Mexico, which seeks the feathered headdress of Montezuma, the Aztec ruler deposed by Spanish conquistadors, now in Vienna’s Museum of Ethnology.

Appealing to Egyptian pride, Hawass defends TV appearances that show him opening tombs and chambers, sometimes with an axe.

“You want a foreigner to open them?” he said.