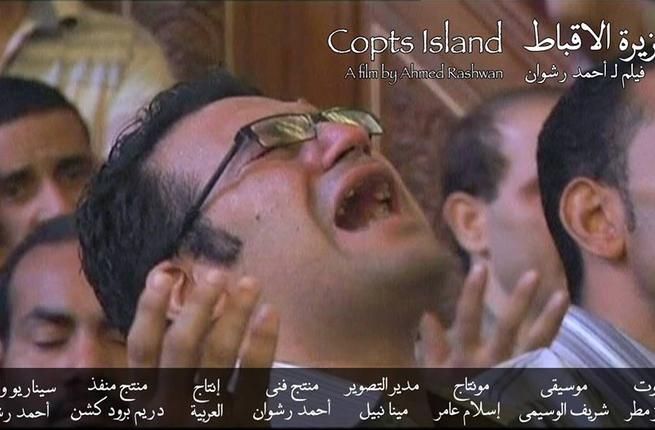

Released in May of this year, Copts Island (Jazeerat Al-Akbat), is a documentary directed by Ahmed Rashwan in which the filmmaker traces the journey of today's Coptic Christians. The film also speaks to several developments in the way the Coptic community has been portrayed throughout the history of Egyptian cinema.

Released in May of this year, Copts Island (Jazeerat Al-Akbat), is a documentary directed by Ahmed Rashwan in which the filmmaker traces the journey of today's Coptic Christians. The film also speaks to several developments in the way the Coptic community has been portrayed throughout the history of Egyptian cinema.

While Egyptian cinematic history has approached Coptic issues and characters in a variety of different ways, a more in-depth look shows that today, documentaries are perhaps the most effective method for objectively portraying Egypt’s Christians.

Copts Island employs enormous research efforts as it includes a wide range of guests and analyses paralleled with equally impressive aesthetic and human dimensions. As such, the film serves as a historical document which tops the list of post-revolutionary artwork.

Inspired by the concept of the biblical stations of Jesus, Rashwan divided the movie into scenes that embark upon eleven separate journeys. Each segment addresses a different political phase of post-revolutionary Egypt, yet the similarities in titling jeopardises the strength of each scene’s individual impact.

Still, Rashwan's characters are remarkably diverse. While most of them represent the middle class, their unique traits force the audience to revisit many common misconceptions of Copts and invite viewers to reconsider prejudice towards the community.

Rashwan looks into the many layers of Coptic identity in Egypt: from analysis of motivations behind Copt’s immigration – specifically to the American state of Georgia – to the political struggles of chronicling their events. Rashwan does not omit the political activism of young Copts outside the authority of the church either. He includes the incidents of Moqattam and Maspero, the death of Pope Shenouda, the rise of Islamists and the death of young Copt Mina Daniel and his transformation into an icon of the Egyptian revolution.

The film equally looks into a multitude of events that have led many Copts to take the decision to immigrate or to change their political affiliation after the removal of former president Mohamed Morsi, starting fresh with the new regime.

As we watch the movie, it is impossible not to notice the director's several political inclinations with which we might either agree or disagree. However, what remains important are Copts Island’s values, which are as powerful as the cinematic advantages that this documentary adds to Egypt’s cinematic history.

History: Between reality and propaganda

Online resources provide a large number of articles and studies related to the image of Copts in Egyptian cinema. The library of Cairo's Academy of Arts along with several other universities are filled with masters' theses and dissertations surrounding this topic, with most of the works addressing the issue in a chronological manner, which is unfortunately the preferred angle of study in Egypt.

Nothing is easier than listing the general features of an era to determine the political direction and assess the works that have been created. Though the chronologic approach to the topic is not completely invalid, it presents the director as a mere agent of whatever the state has seen fit at a given point in history.

In this regard, most of such studies praise cultural diversity and liberalism in Egypt during the 1930s and 1940s, presenting Copts as equal partners in a multicultural country. In movies during this time period, the only indicator of a characters' religion was in his or her name. The same continued throughout the 1950s, years known for cinematic romance and melodrama, with films focusing on love and suffering lovers, within which Copts were not depicted any differently from anyone else.

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, however, the narrative began to change. Scriptwriters and filmmakers began mirroring political orientations and promoting the concept of the unity of Egyptians facing a foreign enemy. We find such themes in films such as Palace Walk (Bein Al-Qasrein), a 1956 movie directed by Hassan Al-Imam Al-Nasser, and Saladin the Victorious (Al-Nasser Salah Al-Din, 1963) directed by Youssef Chahine.

Moving forward in time, the authors of many studies criticise the films of the 1970s and 1980s, pointing to the marginalisation of Coptic characters who were often depicted in supporting roles such as the friends or neighbours of the protagonists or other primary characters.

In their turn, the 1990s' propaganda-filled films were immersed in hostility towards extremists, with Copts being integrated at a very superficial level.

The most iconic representative of this trend is The Terrorist (Al-Erhabi), directed by Nader Galal and with script by Wahid Hamed. This 1994 production stands strong against fanaticism in its broad sense, presenting a Coptic family whose religion demonstrates itself on two diverging levels: tolerance embodied by the husband and fundamentalism personified by his wife.

The Terrorist was one of the first attempts to criticise the stereotyping of Copts in artistic works. In fact, this film paved the way for other more mature cinematic portrayals of the Coptic community, surfacing at the beginning of the new millennium.

Films produced in the 2000s, however, required some thought. Over the past three years, many mediocre directors opted to follow a wave of propaganda, passing up on displaying actual religious discrimination in favour of displaying a state-sponsored narrative. Other bolder and more mature filmmakers presented Egypt’s Christians on the screen as they are in society.

Among the few exceptional works constituting an important legacy in representing Copts in a realistic way are I Love Cinema (Baheb Al-Cima), a 2004 film directed by Osama Fawzy, Yousry Nasrallah's 2008 movie Fish Garden (Geneinet Al-Asmak) and One-Zero (Wahed Sefr), a 2009 film directed by Kamla Abu Zekri with a screenplay by Mariam Naoom.

Despite this reservoir of movies, it is still safe to conclude that documentaries are the most ideal forms of film to objectively portray the marginalisation of Copts. This is a result of low costs – the expenses of producing a documentary do not compare to those associated with a feature film – and the fact that a documentary is not bound by censorship rules or market requirements and trends.

Copts Island recently screened at the Cairo Opera House's Creativity Centre and has understandably attracted a large audience. The film is likely to garner a similar viewership as last year's Jews of Egypt, a documentary chronicling the history of Egyptian Jews directed by Amir Ramses.