The expected signing of a deal between Iran and the West over the former's nuclear programme -- which would end four decades of Iranian diplomatic isolation -- is not the only challenge that Arab nations are currently facing, according to one of the most informed Western journalists who reports on the Middle East.

The expected signing of a deal between Iran and the West over the former's nuclear programme -- which would end four decades of Iranian diplomatic isolation -- is not the only challenge that Arab nations are currently facing, according to one of the most informed Western journalists who reports on the Middle East.

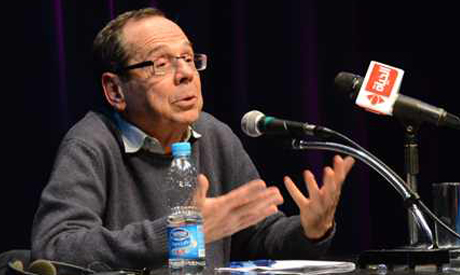

A well-travelled and well-versed journalist whose Egyptian origin and French nationality have granted him multiple in-roads in the region, former editor of Le Monde diplomatique Alain Gresh sees a regional power reshuffle - “and maybe more” – in the making.

The anticipated signing of the Iran deal towards the end of this month is bound to fast track this reshuffle.

According to Gresh it was inevitable a deal between Iran and the West would be reached, although he told Ahram Online that some Western countries are more reticent about it, saying that France, for example, has more reservations about it than say the US.

“It was inevitable because the West, especially Washington, decided that there was a failure in the policies it had adopted on Iran for some 40 years; imposing sanctions on Tehran [in recent years] to secure a stop to the centrifuging activities simply hit a dead end,” Gresh said.

Gresh argues that when the talks started to get serious after years of endless diplomatic give-and-take, US President Barack Obama might not have been very clear about the final deal, or when and how he would get it, but he knew that there had to be a deal with the regime in Tehran that is based on guarantees and understandings rather than confrontation.

The return of Iran to the Middle East, strengthened with a peaceful nuclear programme with Western approval, is bound to bolster the ruling regime in Tehran, says Gresh.

This is not necessarily good news for Saudi Arabia because for the Saudis “Iran remains the enemy.”

This “strategic enemy – with which compromise is not possible” is not going to be a friend overnight, said Gresh.

Gresh argued that the Saudis cannot forgive Iran for the regional power it gained through the Arab world following the US war on Iraq in 2003.

"Iran cast its shadow over the Iraqi regime; it strengthened Hezbullah in Lebanon; it strengthened the Syrian regime that the Saudi regime is in war against; and it strengthened the Palestinian Islamist Hamas.

For Saudi Arabia, Gresh added, the ongoing Iranian influence in Yemen is simply unacceptable.

Saudi political unease, argued Gresh, is understandable. He insists, however, that it is “political and not religious”.

“It is not exactly a Sunni-Shia battle but rather a competition that had been there between the Saudis and Iranians [for decades] dating back as far as the rule of the former Shah, before the Islamic Republic of Iran,” he said.

According to Gresh, when all is said and done, both Iran and the Saudis are acting as medieval rather than Islamic regimes – although Iran is a stronger country in terms of its state hierarchy and military capacity.

This unease of the Saudis towards Tehran will not be easy to dispel, and the Americans might have to offer considerable reassurances, Gresh said.

These reassurances, he argued, cannot include putting a hold on the deal with Iran as the Saudis and Israelis have been attempting to do.

For the US, Gresh added, it has to do with the American defeat in Afghanistan and Iraq and Washington's wish to exit this venue as part of a stabilising deal.

“In Afghanistan as in Iraq the Americans and the Iranians need to work together,” he stated.

Gresh insists that the talks between the west and Tehran were never just about Iran's nuclear programme.

According to Gresh, the US wants to see Iran offer less vigorous and open support to Hamas in order to placate Israel, but even if Iran does so this would not mean that Iran and Israel can overcome their deep and strategic differences – at least not immediately.

In any case, Gresh argued, Israel wants to keep Iran as “a potential aggressor”. If this assumed aggressor is no more, he added, Tel Aviv could be faced with that which it really fears: “the growing international campaign to boycott Israel.”

Israel does not want to be the South Africa of this century, he argued, and it is inevitable that if a nuclear deal is announced then Israel would have to reduce its alarmism about the Iranian nuclear programme.

A deal or Israel partly standing down in its war of words against Tehran would not help the Saudi diplomatic attack on Iran as the supporter of destabilising forces.

In Gresh's view, this up-and-coming political confrontation between Tehran and Riyadh is particularly destablising because the region is already experiencing major difficulties with “failing states and expanding militias.”

“The challenges are hard to undermine; they are perhaps the toughest since the fall of the Ottoman Empire” in the early 20th century, he argues.

As for Turkey, the third key regional power today next to Iran and Saudi Arabia, according to Gresh, it is a different game.

Ankara and Tehran, Gresh said, are essentially coordinating policies – despite disagreements on several key issues including, for example, differences on the regime in Syria, or the fact that one country is a Sunni majority state and the other Shia.

Recent political changes in Turkey, argued Gresh, hint at a decline in the regional political fortunes of Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Gresh suggested that the receding influence of Erdogan on regional politics is not just about home-front developments, but also about regional developments related to the declining profile of political Islam.

This said, Gresh added, the fact remains that Turkey is still one of the most stable economic powers in the Middle East, and also remains an expanding power in Africa where it is increasing investment in more African states on regular basis.

Ankara, Gresh argued, would essentially work to expand relations with Iran – while still holding to its strong relations with the Saudis.

According to Gresh, eventually a regional agreement has to be reached among these three capitals, Riyadh, Ankara and Tehran, if they want to see that regional stability is secured and if they want to end the threats of Islamist militias against them such as those currently posed by the Islamic State group.

"This should not be a very tough fight given that “the call of ideology in today’s world is no more.”

“But the fight has to be serious because what we see now is a situation where, for example, the Saudis are working with Al-Qaeda in Yemen and are working with Jabhat Al-Nusra in Syria,” Gresh said.

It is too early in the game to decide how this tri-lateral deal between the three main capitals in the area could be reached but it would certainly be a result of a process in which Turkey and the US would play a key role, Gresh suggested.

Egypt could possibly join this deal, Gresh argued.

“The problem with Egypt is that it has been too focused on its internal affairs or on the many problems it faces in its immediate neighbourhood,” he said.

It is hard for Cairo now, Gresh said, to divert its attention from the situation in Sinai or in Libya to opt for involvement in wider and further regional conflict spots.

Eventually, Gresh argues, if things stabilise then Cairo can start to widen the scope of its regional engagement.