Mawso'at Al-'Onf fi Al-Harakat Al-Islamiya Al-Mossallaha (Encyclopaedia of Violence in Armed Islamic Movements) by Mukhtar Nooh, Sama Publishing, Cairo, 2014. 535 pages

Mawso'at Al-'Onf fi Al-Harakat Al-Islamiya Al-Mossallaha (Encyclopaedia of Violence in Armed Islamic Movements) by Mukhtar Nooh, Sama Publishing, Cairo, 2014. 535 pages

The author of this encyclopaedia hammers on a central theme: how armed Islamist organisations of the past 50 years tirelessly form continuous patterns -- not only in terms of the ideas they embrace and the methods they employ, but even in the persons carrying out the work who, once released from prison, join other organisations with identical ideas.

Having begun his adult life as a member of the Muslim Brotherhood in the 1970s, repeatedly incarcerated and eventually becoming a lawyer specialising in political Islam, Mukhtar Nooh knows his topic in depth. He kept a vast archive of interrogations, arraignments, prosecution papers and court verdicts spanning nearly half a century of cases, which has enabled him to achieve this encyclopaedic endeavour.

His work extends beyond merely offering a compilation of data to additionally analysing the ideas held by violent organisations and the links they shared in the political arena during Egypt's Sadat and Mubarak eras. The reader is faced with an unprecedentedly comprehensive tome which, more importantly, relies upon documents and official sources. As for the author, he is a witness, a participator, a maker of events, a lawyer in some cases and a detainee in others.

Through its three sections, the encyclopaedia comprises four cases forming a panorama of violence and bloodshed. The first is the Military Technical College 1974 case, which the author describes as "the 20th century's first coup d'etat under the Islamist label". The founder of the Islamist organisation behind the case is Palestinian Salih Sirriya, who hailed from the ranks of the Iraqi branch of the Brotherhood and is now viewed – even after his execution in connection with that case – as one of the biggest Al-Qaeda intellectual authorities.

It is noteworthy that late Egyptian president Sadat began during that period to release Brotherhood members from the prisons where they had been languishing since Sayed Qutb's execution in 1965. This strategy aimed to quell the influence of the Leftist and Communist ideals spreading among university students and the larger political arena by allowing Brotherhood members to exercise political action.

So, when Salih Sirriya attracted a number of youths in the early 70s to the idea of Jihad -- then anchored in the premise that the only way toward an Islamic state was through armed force -- the plan's simplicity verged on naiveté: storm the armoury of the Military Technical College in Cairo (where a number of cadets were organisation brethren), seize weapons and vehicles, head for the Arab Socialist Union headquarters, arrest Sadat attending a meeting there, seize the Radio and TV Building and announce a statement.

Sirriya first tried to secure the Brotherhood's consent and support, but the organisation declined due to the "honeymoon" it was enjoying at the time with the Sadat regime, which was to imminently release its members from prisons. As documented in the interrogations, Sirriya was keen to refute the Brotherhood's connection to the plan but could not, however, deny his political relationship with its leaders.

The second case tackled by Nooh was the 1977 killing of Sheikh Mohamed Al-Dhahabi, ex-Egyptian minister of endowments, at the hands of the Jama'at Al-Muslimin group, known in the media as Al-Takfir wal-Hijra (Condemnation of Infidelity and Exile).

Shukri Mustafa, the group's leader who emerged from the Brotherhood's ranks, was deeply influenced by the ideas of Sayed Qutb and Abul Ala Maududi which condemn society as infidel and hence call for the believer's isolation from it.

Over the two years following its formation, the group carried out over 10 killings, assassinations and liquidation operations until it kidnapped Sheikh Al-Dhahabi from his home to bargain with the state: in exchange for his freedom, they demanded the group's members released from jail, an LE200,000 ransom in cash and public apologies from the press for all news stories about the group, which the latter deemed as fabrications and lies.

After the failed operation, the killing of Al-Dhahabi and the arrest of the group's members, the defendants' stance during interrogations remains noteworthy, as they expressed happiness with the killing, accusing the rulers and society at large of infidelity. Also interesting are the relations and open channels between the state, represented in the security services, and the group – as revealed by the interrogations.

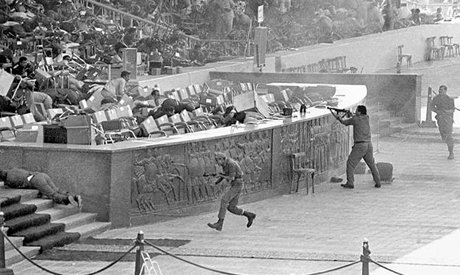

The trail of violence continues in the encyclopaedia's third and last section which focuses on the two Jihad cases. The first one, in 1979, occurred when a group of youths attacked the Cypriot embassy's guard, killing him and seizing his weapon. The second case took place only two years later: the 1981 assassination of Egypt's president Sadat.

The author asserts two points of the utmost importance, pertaining as they do to the role of the security apparatus in the four aforementioned cases. The first is the absence of information in a way that incriminates said apparatus, as all the cases were reported, and thus unveiled, for reasons unrelated to the security service.

The second point is the security service's inclination to distance itself from serious follow-up on the activities of armed organisations. According to the author, it instead executed a "let him drown" policy with Sadat since he had unilaterally decided to release Brotherhood members and allowed them to exercise political activities, until it was too late.

With this voluminous work, the reader is most certainly faced with an unprecedented achievement which, first and foremost, chiefly relies on security and judicial sources.