When Islamic scholar Zaghloul el-Naggar recommended the consumption of camel urine, describing it as an Islamic remedy for incurable diseases on a television show last month, the channel’s switchboard was bombarded with angry phone calls within minutes.

“Medicine is based on evidence ... Surely I don’t need to be teaching you this?” well-known doctor Khaled Montassir told Naggar on the show, barely concealing his frustration. “I am not happy with what’s happening to Muslims because of your ideas.”

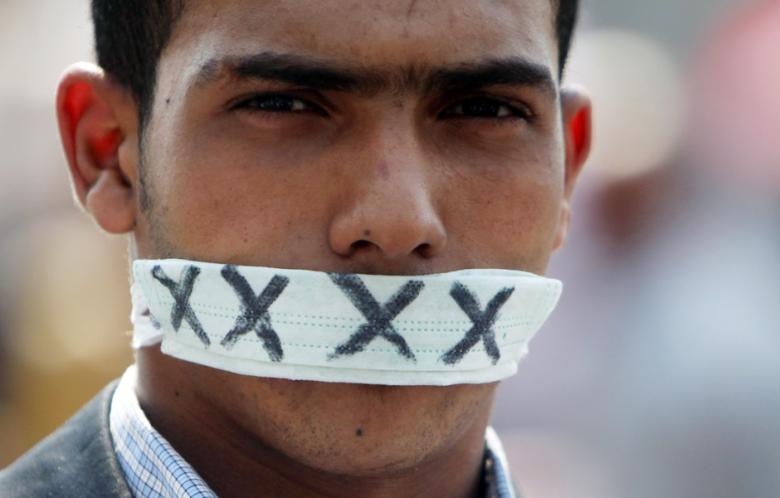

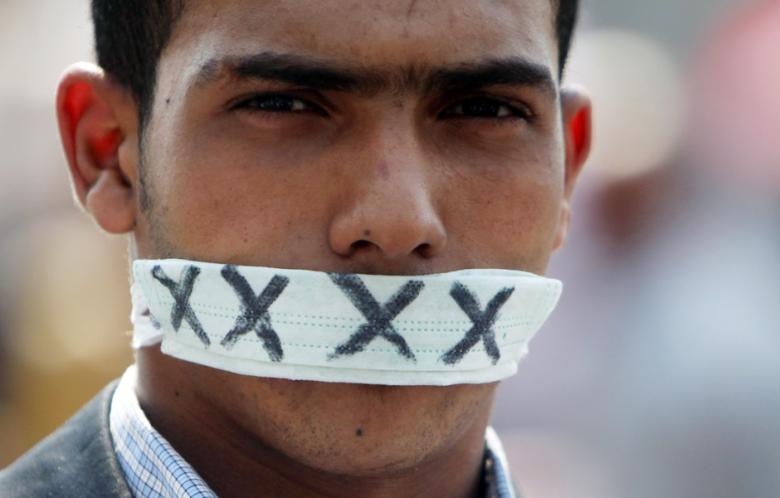

Egypt’s media, once tightly controlled by the state, has become a free-for-all platform for ideas, theories and advice, which can range from the ignorant to the bizarre and to what some see as outright dangerous.

Inevitable

Much of the talk is the largely innocuous and inevitable product of democratic reforms promoted by the revolutionary movement of the Arab Spring, opening up space to new voices.

But some Egyptians are concerned that such freedoms are being exploited by hardline Islamists and self-appointed religious experts to extend their influence in a society still finding its feet after months of turmoil.

The Grand Mufti, Egypt’s most senior Islamic legal official, has denounced edicts made by unqualified preachers and declarations such as those suggesting that treating the ill with camel urine is somehow an Islamic teaching. “Such talk is wrong,” said spokesman Ibrahim Negm.

Egypt’s Islamist leader Mohamed Mursi won elections in June promising to be a president for all Egyptians, and one of his big tests will be how he deals with radicals whose ideologies worry mainstream Muslims and minority Christians.

His allies in the Muslim Brotherhood, which has a conservative vision of society while vowing to support democracy, are under pressure to take a clear line.

“The Brotherhood is now in power. They need to act as rulers and ... state their position regarding such radical views and preachers,” said political analyst Nabil Abdel Fattah.

When Mursi’s predecessor Hosni Mubarak was in power, the government strictly policed the airwaves, and managers of private TV channels were often harassed by state security if their guests displeased the authorities.

The restrictions stifled pro-democracy activists and criticism of the Mubarak regime, but they also put a lid on advocates of religious extremism.

While some Egyptians welcome today’s lively public debates, others say that airing fanatical or eccentric ideas makes them seem more acceptable and encourages bigotry and intolerance, sometimes playing on ignorance in a religiously conservative society where many are illiterate.

Government officials and media commentators were quick to condemn Abdel Moneim el-Shahat, a well-known ultra-orthodox Salafi Islamist, when he suggested last year that ancient statues including the Sphinx guarding the Pyramids of Giza be covered up as they might be idolatrous.

In February, Shahat suggested that soccer matches should be forbidden and only horse and camel races allowed, seen as part of his drive to strictly emulate the days of the Prophet Mohammad and shun modern activities.

Other Salafi leaders have said it was against Islam to salute Egypt’s flag or to sing the national anthem, called on Muslims to declaim as an infidel anyone who is “secular, liberal or modern”, and argued against English being taught in schools.

The Grand Mufti has condemned such declarations in the name of religion.

“Untrained amateurs who attempt to issue fatwas are not authentic scholars, and their fatwas are more like independent unscholarly statements made according to their whims and desires,” his spokesman Negm said.

Indications

While there have been few indications that any of these suggestions have been taken seriously, they alarm moderate Egyptians who worry that they are the thin edge of the wedge at a particularly sensitive time.

A 100-strong assembly of scholars, politicians, academics and others is drawing up a new constitution to determine the role of Islam and Islamic law in Egypt’s government and legal system. Liberals and Islamists have been at loggerheads.

Moderates also are concerned about how the riot of ideas may be subtly influencing the way people think and act.

Many viewers were indignant when the female host of a popular talk show agreed to a request from Assem Abdel Maged, a leading figure of the ultraorthodox Salafi group al-Gama’a al-Islamiya, to be interviewed through a screen because she was not wearing a veil.

“It would have been better for Hala Sarhan to apologise for not running this shameful episode than to accept this situation,” wrote one viewer on YouTube, where the interview was shown.

Muslim lawyer Sherif el-Hosseiny, 35, reflected the views of many Egyptians by saying: “One of the reasons I risked my life in protests last year is to have the country go forward and definitely not have it go backward to pre-historic times.”

But for others, the public outcry shows a society still uncomfortable with an open democracy.

“In the United States a film was produced insulting the Prophet Mohammed (PBUH) ... and here too we have people who express rational and irrational views,” said political analyst Mustafa al-Sayyed, adding the government had a duty to promote moderate thinking.

“This is the price every society has to pay for freedom of speech,” he said.